Between the bridges – Beachley to Sudbrook and beyond

Between the bridges – Beachley to Sudbrook and beyond

Rhoda returns to the Severn Estuary, this time exploring the shore between the Severn Bridge and the Prince of Wales Bridge, to uncover more tales of river crossings and their lasting impact on the fortunes of local communities. From heritage fisheries and whale bones to gushing springs and the UK’s longest overhead power line span, this stretch of coastline is full of surprising stories waiting to be discovered.

Across the marshes looking towards the Prince of Wales Bridge

Introduction

Another sweltering day was on the cards for my monthly estuary walk. Still, I figured that by doing the ‘mirror image’ of my last route — from Aust to Severn Beach — but this time on the other side of the Severn, between the two bridges, we might at least find a bit of shade beneath the structures themselves.

Keen to build on the stories we’d uncovered during that previous walk, I set out with Geoff, my trusted companion and husband, to explore the Severn shoreline between Beachley and Sudbrook. Much of our route followed the Wales Coast Path, winding through landscapes so well documented by the Living Levels project.

I hope you enjoy reading about our day out as much as I enjoyed walking and researching it — preferably with a cool glass of something refreshing in hand. (There may even be a few ideas for that later…)

The Severn Bridge from near Beachley Point

Underneath the arches: the Severn Bridge undercarriage

The river crossings – the Beachley Slipway and the Severn Bridge

My attempt at a ‘commercial’ photo shoot!

Beachley – the old and the new crossings

Parking in the shadow of the Severn Bridge alongside a tangle of undergrowth, a ‘Danger: sea wall unsafe – keep away’ wasn’t quite the welcome I’d expected. The Old Ferry Inn which I remember seeing during a photo shoot twenty plus years ago seemed also to have lost its charm despite efforts to renovate part of the building as a conference centre. The Severn Area Rescue Association (SARA) station next door was eerily quiet too, despite various noticeboards highlighting the incredible work that operates out of this otherwise unremarkable building.

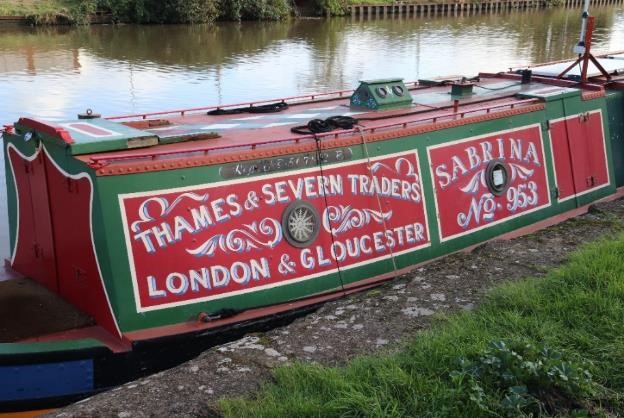

Then, we turned to look at what we had come to see — the Beachley to Aust crossing, the other end of the Old Passage that we’d encountered on our last walk. The wide stone ramp of the old slipway sloped gently downward, as if inviting us to step into the chocolate-brown waters of the Severn. No ferry today, though – the last car ferry crossed the estuary here nearly sixty years ago, on the day before the Severn Bridge opened. However, many older people still have happy memories of travelling on this ferry. Kay Powell, a former SEP Chair, excitedly recalled her childhood experiences. In our recent get-together she recounted her summer outing from Cardiff to visit her great aunt in Portishead. ‘The most exciting thing was when my dad got a car, and we’d go via the Aust Ferry. There we could see the sea gently receding. And there we were, counting the numbers of cars back, seeing if we’d get on the next ferry. And actually getting onto that with the turntable and going across to Aust…an amazing experience!’ Kay is one of many generations to have used this historic crossing — a route once travelled by Roman legions and 12th-century monks. As we watched the swirling muddy waters recede at the bottom of the slipway, it was easy to understand though why several fatal crossings had occurred here in the mid-nineteenth century — and why Daniel Defoe reportedly chose to avoid this crossing, opting to travel through Gloucester instead.

This crossing, however, is no backwater. It still serves as the slipway for SARA and other watercraft. During our visit, the slipway also served as a spot for a local angler to fish and a mooring for the fishing boat Helen Louise. Its owner eagerly shared stories of fishing for cod, conger eel and other fish in the Severn and fondly recounted crossing the old ferry as a boy, when he and other kids would hop on and off to catch a ride to the other side. “It hadn’t been the same once the bridge was built, but at least the pilots [many of whom were called Jack] were able to find work operating the toll booths,” he reflected. Later, as I focused on capturing better angles and shadows for my photos, I was distracted by the buzzing of a small drone overhead. Then, to my surprise, a sleek Bentley sports car smoothly glided onto the slipway. The slipway had become the unexpected backdrop for a commercial photo shoot! As you can see, I had a go at some glitzy photos, with moderate success.

Beachley Point – connections

After a short stroll along a leafy track, with occasional glimpses back toward the Severn Bridge, we arrived at a rather scruffy spot near the National Grid’s Beachley Compound, overshadowed by the striking anchor pylon soaring an impressive 148 metres above. At just 10 metres shorter than Blackpool Tower and significantly taller than any of the ‘skyscrapers’ in the cities surrounding the estuary, this pylon — along with its twin at Aust —supports the longest overhead power line span in the UK, stretching an impressive 1,618 metres. We craned our necks to take in the sheer scale of this giant electrical bridge stretching across the Severn!

We hadn’t come to admire the pylon, however — spectacular as it was, but rather to take in the views of the estuary and catch a glimpse of ‘Tracey Island,’ which I first spotted during my sail on the Waverley last summer. After some careful negotiation, avoiding stinging nettles and brambles, we eventually made it to the viewpoint at Beachley Point. Beyond a carpet of brown seaweed and glistening, slippery mud, the faint silhouette of a ruin perched on a rocky hummock came into view—the island known by so many names – Chapel Rock, St Twrog’s Island, St Tecla’s Island…and now Tracey Island, of course! Despite the falling tide, there was no chance we’d attempt to reach the ancient ruins of this medieval holy site today, just as generations of pilgrims are said to have done in the fourteenth century. I could certainly understand why this site once served as a refuge for hermits. However, with so many modern intrusions visible across the mudflats — pylons, warehouses, and other stark reminders of the 21st century, it was difficult to imagine the solitude that once defined this place.

The impressive anchor pylon near Beachley Point

Across the seaweed towards the island of many names

View across the mudflats towards the Wye Estuary

Black Rock – tidal landscapes, lave fishing and estuary connections

After retracing our steps, we drove to Black Rock, where we enjoyed our picnic lunch accompanied by spectacular views of both bridges stretching across the estuary. The scene was made even more striking by the vast intertidal zones laid bare by the low tide. With the mudflats and seaweed-draped rocky reefs exposed, the foreshore revealed a captivating and ever-changing landscape, though a treacherous one, as signalled by the white lighthouse that stands guard over the offshore reef (Charston Rock) hidden beneath the water at high tide. Later, treading carefully, I explored the edge of the marsh and was fascinated by its intricate microtopography. Dense tufts of saltmarsh grass rose on small hummocks, criss-crossed by a network of hidden and shallow hollows, some still holding water. It was a remarkably complex and diverse ecological system — shaped by a long and layered history of both erosion and deposition. Even just inland from the true marsh edge, isolated stems and clumps of cord grass were beginning to take hold, pushing up through the drying cracks in the mud.

View upstream to the Severn Bridge from Black Rock

View downstream to the Prince of Wales Bridge

Cordgrass attempting to colonise the mudflats

Suddenly, we spotted one of the famous lave net fishermen striding across the mud, likely returning from the channel after a session of fishing. He carried his distinctive willow-framed net, just visible in the photo below. Although now a catch-and-release heritage fishery for salmon — somewhat contentiously — this centuries-old tradition is still upheld by a few dedicated local fishermen at this heritage site. According to their Facebook page, the group has built quite a following, and their videos are well worth exploring. You’ll find everything from explanations of how the nets work to footage of their fishing finds, including ancient fish traps, curious debris, most unwanted items, and more. If you’re interested in learning more, they’re hosting a special open day on 25 August. To celebrate this enduring tradition, there’s even a striking, larger-than-life oak sculpture of a fisherman and salmon, carved by local chainsaw artist Chris Wood, proudly displayed near the picnic site overlooking the estuary — a piece we stopped to admire.

A lave net fisherman returning to shore with the Black Rock lighthouse in the background

The Fisherman sculpture at Black Rock picnic site

Nearby, facing out to sea, another sculpture from the People and the Landscape series caught our eye — standing proudly atop the remaining stump where the rail-steam ferry once crossed to New Passage, which we’d visited just a month earlier. The Engineer — a distinguished figure in a smart coat, hat, and walking stick, holding a model of a factory in his left hand. This sculpture pays tribute to all those who worked on the Severn Tunnel, the two bridges, and the seawall that protects the Gwent Levels. It’s inspired by the intrepid and resilient 19th-century engineer Thomas A. Walker, who completed the Severn Tunnel and oversaw the development of the neighbouring village of Sudbrook — where we were to head off to next.

The Engineer sculpture standing proud above the old Black Rock slipway

The imposing Victorian Sudbrook Pumping Station

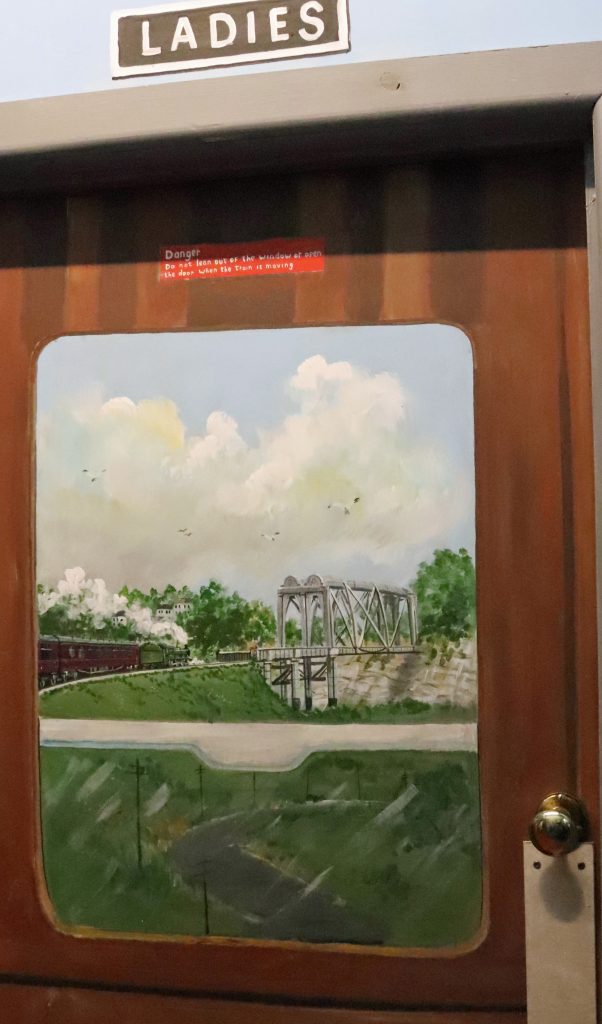

The view on the door of the Ladies toilets

Sudbrook – discovering more Severn heritage

The shade along the leafy path gave us some much-needed relief as the temperature climbed, and it was with a certain relief that we reached the edge of Sudbrook. After passing some nondescript modern developments, we found ourselves on a long street lined with cottages — part of Walker’s workers’ village from the nineteenth century, built during the construction of the Severn Tunnel. With their colourful façades and flower-filled gardens, it was striking to think these homes had once been humble dwellings for the labourers working on this ambitious project – one we still rely on today, as trains whisk us through the Severn Tunnel in under four minutes on our journey to and from South Wales. As we approached the imposing red-brick Sudbrook Pumping Station rising high above the cottages at the heart of the village, we could hear the steady whirring of machinery. No fewer than fourteen pumps are required to keep 50 million litres of water out of the tunnel every day, and, as Network Rail informs us, these must be replaced every three decades. As we learnt later from our visit to the local museum, confronting and containing the ‘Great Spring’ was one of the great engineering feats of the late nineteenth century.

The Sudbrook Interpretation Centre is quite a gem and is worth a visit, although tucked away in the corner of the Sudbrook Non-Political Club, it wasn’t that easy to find. Though we seemed to enter through a back door, we were immediately transported into another world — greeted by colourful murals in the entrance hall celebrating railway triumphs and journeys. Even the toilet door was painted, as you can see below.

The exhibition room, though modest in size, held a fascinating and eclectic mix of local stories and memorabilia that we eagerly explored. Alongside informative display boards lining the walls were towering stacks of scrapbooks, school projects, and old photo albums. Glass cabinets showcased an array of finds from the mud of the River Severn—many with real historical significance. There was even the horn of a medieval cow and a whale bone from a whale that washed up at Sudbrook a century ago, in 1925!

We took our time delving into the material — not only was it genuinely fascinating, but it also offered a welcome cooling refuge from the sweltering heat. I have to personally thank the Caldicot and District Historical Society, not just for curating such an engaging collection, but also for the thoughtful touches like the tea and coffee-making facilities. If only every community around the Severn Estuary had such a valuable and lovingly maintained resource.

The Prince of Wales Bridge – yet another perspective!

After enjoying the cool respite of the museum, we stepped back into the searing afternoon heat to complete our bridge-to-bridge journey — determined to reach the Prince of Wales Bridge on the Welsh side of the estuary by foot. Skirting behind more of the original workers’ cottages, we eventually found ourselves crossing a football pitch by the water’s edge. But this was no ordinary pitch — it stands within Sudbrook Camp, an ancient hill fort likely dating back to the Iron Age. Over the past two thousand years or so, significant coastal erosion has claimed much of the southern ramparts, now lost to the sea. Perhaps something the residents of the extensive new housing estate to the west of the village — partly nestled within the remaining ramparts — should be mindful of, especially given the size of some of the debris scattered along the strand line on the marshes.

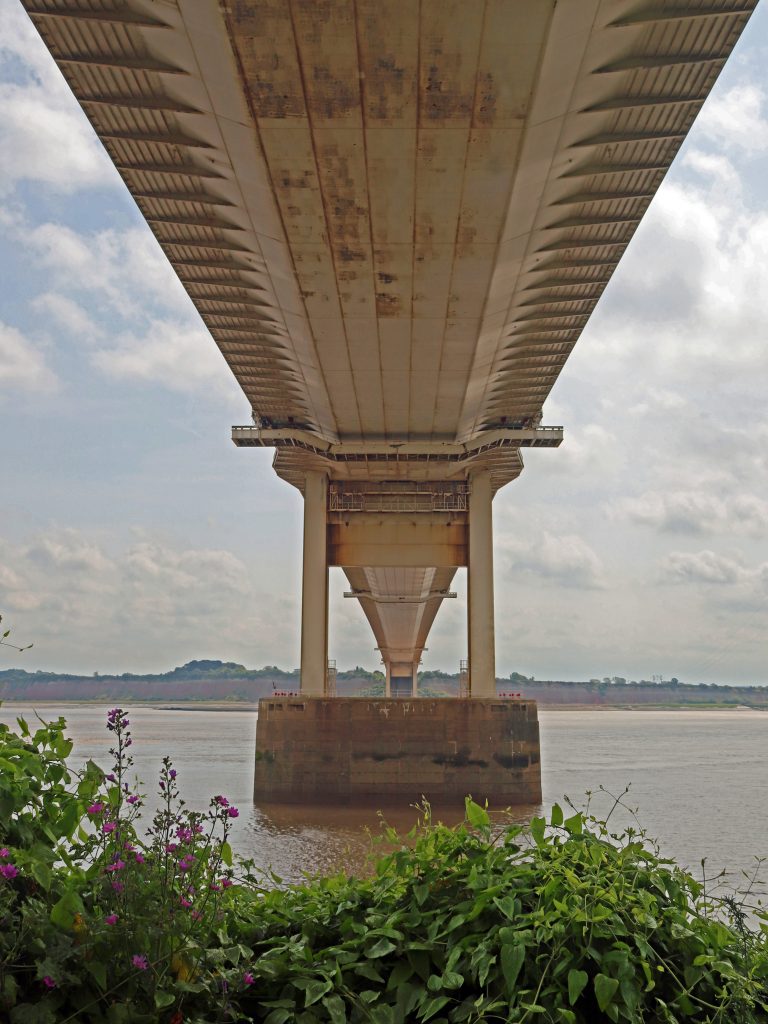

With the sun beating down, I must admit I struggled to walk the rest of the path, which, being wide open to the coastal marsh, offered no shade. The ever-changing marshes and sweeping coastal views kept me going, though I found myself increasingly distracted by the roar of traffic growing louder and more thunderous as we neared the bridge. After nearly emptying our water bottles, we finally reached our destination — and the cool shade beneath the bridge’s undercarriage was a truly welcome relief.

Amid the relentless noise of traffic, focusing on taking meaningful photos was a challenge, but I hope the ones that follow convey the sheer scale of this mighty structure from our vantage point — a strikingly different perspective from what we’d seen on the other side of the estuary only a month ago. Here at Caldicot, the bridge twists sinuously across the marshes, stretching into the distance like a giant centipede resting on towering pillars. We savoured our final glimpses through the arches, offering an intriguing view of this impressive feat of engineering, before making our way back to Black Rock — via the wonderful refuge of the Sudbrook Interpretation Centre, of course.

Housing nestling behind Sudbury Camp – note the storm debris on the marsh

The Prince of Wales bridge meandering above the marshes at Sudbrook

Further reflections and conclusions

Whether it’s an unexpected perspective on a familiar place or a fresh angle on a well-known structure, there’s always an element of surprise that keeps us engaged as we explore each stretch of this remarkable estuary — and this walk was no exception. It was far from a mirror image of my previous walk, though there were many similarities and parallels — not least the sweltering heat on both occasions. But new stories had emerged on this side: tales of the traditional lave net fishery, for instance, and the unexpected popularity of the old Beachley slipway as a photo shoot location.

The strategic importance of river crossings — and their influence on the ups and downs of coastal communities — is something both stretches of the estuary share. Sudbrook, for one, quite literally owes its existence to the construction of the Severn Tunnel. Today, it’s a far cry from Walker’s original ‘new town’ plans, but one thing hasn’t changed: the Great Spring still needs taming. Indeed, next time you crack open a Budweiser, Stella, or a pint of Welsh bitter, there’s a chance you’re actually drinking water from that very spring — it now supplies the local brewery at Magor! As for me, after a scorching day out, I gave the beer a miss and opted for a tall glass of my trusty Severn Beach/Pilning cordial, the perfect way to reflect on yet another memorable day by the estuary.

An intriguing perspective through the arches of the Prince of Wales Bridge

Further information

Check out this link for a stunning photo of a bridge section being installed over the ferry slipway at Beachley

Living Levels Loop and Links Walk 5 – Caldicot to Black Rock loop

Sudbrook and Portskewett trails through the ages

The Severn Estuary Forum Programme is out now!

We are delighted to announce the release of the full programme for the Severn Estuary Forum 2025, taking place on 3rd July in Weston-super-Mare. This year, the forum brings together a rich mix of expert talks, panel discussions, and community stories.

Register for the forum and explore the programme here:

Newport Wetlands – great expectations from a post-industrial landscape

Written by Dr Rhoda Ballinger, SEP Chair

In my April article I explain what’s so special about the RSPB Newport Wetlands Reserve, the ‘jewel in the crown’ of the Gwent Levels, and discovers some of the fascinating history and archaeology of the coastal landscape around Goldcliff.

East Usk Lighthouse

Introduction

Only a month ago, there were major celebrations to mark the twenty-fifth anniversary of the construction of the RSPB Newport Wetlands Reserve. Created from heaps of polluted ash from the nearby Uskmouth Power Station, this conservation site was part mitigation for the loss of intertidal habitats caused by the creation of the Cardiff Bay barrage. Amazingly enough, the National Nature Reserve is now frequently viewed as the ‘jewel in the crown’ of the Gwent Levels and is famous for its shrill carder bees and its booming bitterns, amongst many other species.

Keen to put my recently acquired knowledge from a RSPB winter wader ID course to the test, and with ‘great expectations,’ I headed out with Geoff, my husband, to the reserve at the western end of the Caldicot Levels. We planned to explore some of the reserve as well as the coast around Goldcliff, famous for its historical and archaeological significance as well as its nature conservation value. And, once again, I’m delighted to be able share some comments from a local person with in-depth knowledge of and enthusiasm for the area in my article. Mike Pointon is a keen amateur naturalist with a particular interest in birds, who founded the Friends of Goldcliff Lagoons back in 2014. He’s not only worked alongside others to improve facilities for birdwatchers but also leads walks and has carried out monthly WeBS and hightide counts at the lagoons.

Extensive intertidal marshes, east of the Usk

The Reserve

As we planned the details of our walk in the coffee shop in the Visitor Centre at the start, the first avian challenge momentarily appeared – a distant dark speck flitted amongst the reeds at the far end of the pond. The elusive creature darted between the reeds, testing the limits of my DSLR camera’s zoom lens and a rather basic pair of binoculars we’d bought. The bird appeared quite small and possibly fluffy. Perhaps it was a baby bird? It was on its own, though, and it certainly didn’t resemble any of the species I’d seen on my bird ID course. Eventually, it swam closer. It continued to scurry nervously from one clump of reeds to another, teasing its small audience of onlookers inside the cafe. Eventually, it posed for a short while in front of us, giving me just enough time to capture a quick photo. Then as quickly as it had emerged, it disappeared into the reeds at the far end of the pond, having completed its morning performance. It was a little grebe. Well, I think it was. Certainly, so much smaller and fluffier than the great crested grebe which I’d recently seen gracing the waters of the Lisvane Reservoir in NE Cardiff. Wow! If that was the overture, what was the main performance going to be like?

We eagerly ventured along the waymarked paths into the reserve to do a hybrid walk, encompassing part of the ‘Wetlands Experience’ and the ‘Estuary Trail’ so we’d also be able to see Goldcliff as well on our short visit.

As we walked towards the shore in the reserve, we were surrounded by a sea of golden reeds, wafting gently in the breeze. Ribbons of vibrant green new growth edged the long unnaturally straight water areas which gleamed bright blue in the sun. Apart from a squishing sound as we walked across a floating pontoon amidst the reeds, it was relatively calm and peaceful. Perhaps a little too calm and peaceful? We stopped at various lookout posts where information boards tantalisingly displayed a range of possible birds we could encounter. No birds in sight today though. Hmmm. Overhead the towering pylons and power cables dominated the skyline and were reminders of the adjacent industrial site and the area’s continuing importance for power generation. Still no birds. The forbidding industrial backdrop, the scene for several episodes of Doctor Who loomed large behind the haven of the reserve. Still, no birds….

Then, just as we were about to move on, a few large birds swooped down and landed on the water in front of us. Certainly not a flock, but at least a handful of birds. And … they were easily recognisable! Canada geese! May be a grade one entry though, given their prevalence across our shores. However, as I found out later, they’re not a native bird, having been introduced from North America some 300 years ago. After some rather amorous advances between a couple of these geese, all too brief for my camera skills, I was able to capture some shots of these elegant birds, including the one here.

A little grebe entertains the café clientele

Canada goose on the reserve

East Usk Lighthouse

Blacknore lighthouse at Portishead

Walking further towards the shore, the lighthouse beckoned. However many times I’ve been to the reserve, I always seem to find myself clicking away, trying to capture a new camera angle and avoid that iconic, some might say, rather hackneyed, image of the lighthouse. Oh dear… yes, that’s my cover photo! On today’s visit, however, the ‘white cone on the water’s edge’ as Peter Finch describes it, was looking particularly fine in the golden light and seemed as popular as ever with the visitors. Glistening white, protected by its very own picket fence, this somewhat diminutive lighthouse looked more as if it belonged in a model village rather than being a working lighthouse. This is the East Usk Lighthouse though, and its light provides a vital navigation aid to ships approaching Newport. Indeed, its importance goes beyond that. It was the first Trinity House lighthouse to use a special valve, enabling the light to turn off and on remotely just using daylight. The most striking aspect to me though on our visit today, was the lighthouse’s resemblance to the Blacknore Lighthouse on the other side of the estuary at Portishead, where I’d visited only a couple of months ago. Back when the East Usk lighthouse was built in the late nineteenth century the structures would have been near-identical twins. Now, following tonnes of disposal of fly ash from the Usk Power Station which buried the legs of the East Usk lighthouse, they’re merely distant cousins!

From the raised embankment at the seaward edge of the reserve, the marshes stretch out as finger-like protrusions into the estuary’s mud. More bird-watching possibilities? Much to my excitement and relief, even with our limited apparatus, we could immediately distinguish the shelduck from the mallards. Fortunately, for us, they were heads down, enjoying the rich pickings of the newly exposed muds! However, even with their characteristic chestnut stripe and reddish bills, the shelducks are still quite well camouflaged against the russet browns and blue greys of the intertidal landscape. So are the curlews, but with their distinctive long, down-curved bills, we were just about able to pick out the odd one. Then, a few gulls flittered across the sky. They took a sudden turn and wheeled and glided onto the silver muds … unfortunately, just beyond the limits of our magnification. Well, at least our bird count had been reasonable. I’d also been reminded of my previous visit, when, thanks to the RSPB guide’s telescope, I’d seen scores of curlews and lapwings jam-packed at the water’s edge here as the tide was receding. Despite our show today and these memories, I was still a little envious of Mike’s memorable moments. These include doing early morning Bearded Tits surveys at Uskmouth and hearing ‘Reed and Sedge Warbler singing, perhaps even a Cuckoo calling and a Whitethroat and singing its rasping courtship song as it dances along the hedgerow’, all ‘whilst the mist rose above the reedbeds.’

Shelducks feeding on the rich intertidal muds

The white specks of coastal birds (gulls, shelducks and a curlew) on the silvery muds

Before we turned back to go on to Goldcliff, we strolled a little further along the coastal path, enjoying the ever-changing shoreline. The West Usk Lighthouse, which once marked the western entrance to the Usk river channel for ships heading to Newport docks, was just visible. Much more noticeable was the massive strandline. This coronet of gnarled driftwood encircled the entire coast, following the base of the embankment. The sheer scale of the mighty tree trunks engulfed in the debris were a stark reminder of the power of the winter storms which have plagued those inhabiting these shores over the millennia. Expecting to see today’s plague, plastic and other litter, I was very pleasantly surprised: there wasn’t any! I found out later that there’d been a litter pick by staff from Natural Resources Wales (NRW) and RSPB only a week or so before as part of Spring Clean Cymru when bags and of bags had been collected.

Looking towards the Usk a prominent strandline backs extensive intertidal marshes

The Goldcliff shoreline

We then wove our way along narrow lanes towards Goldcliff between a patch work of fields lined with deep and dark drainage ditches, a legacy of the Romans and the medieval monks who’d captured and tried to tame this watery landscape from the sea. No environmental impact studies in those days, just the need to provide valuable agricultural land to survive.

Then a small incline gradually came into view. This was the famous Goldcliff, a ‘rocky eminence’ which had caught the attention of the celebrated medieval cleric and celebrated travel writer, Gerald of Wales/Giraldus Cambrensis back in the twelfth century. In Gerald’s account, he’d noted that ‘when the sun’s rays strike it, the stone shines very bright and takes on a golden sheen’ and he’d even suggested that the ‘skilled’ might ‘dig down into the mineral deposits to extract sweet honey from the stone and oil from the rock.’ Centuries later, on our visit, there was no honey, oil nor indeed any gold. Only the rusting plinth of the old Goldcliff lighthouse provided a dash of colour, but even that looked in a sorry state, having lost its lantern in recent years. Not quite the magical place I’d hoped for. A substantive seawall skirts around the cliff and obscures seaviews. Any remains of the old Goldcliff Priory lie were also well hidden within ‘Hill Farm’, behind the sign reading ‘private property, keep out.’

Still, there was a great view from the cliff top and indeed also from the seawall which doubles up as the track of the Wales Coastal Path. Sites of previous walks, wind turbines, docks, piers and even the Prince of Wales Bridge were just discernible across the hazy estuary. Today, however, our attention centred around birds. There were a lot to see – gulls, mallards, shelduck and the odd curlew wading across the foreshore. Perhaps my bird ID was improving after all. Then in flew a flock of seabirds. They swirled and swooped in unison high above our heads before plummeting down to momentarily settle on the distant mudflats. They took to the air again. As the flock twisted and turned, shafts of sunlight caught their plumage. Constellations of seabirds lit up the sky. What a performance and all so amazingly choreographed. I’m just sorry I couldn’t capture any of it on camera or indeed identify the birds themselves.

The only ‘gold’ at Goldcliff – the rusting lighthouse plinth perched on the top of the cliff

The seawall at Goldcliff

As the sun began to sink lower in the sky, a spider’s web of rivulets and channels appeared across the silvery muds and serried ranks of ancient timber poles cast long, dark shadows across the foreshore. The metamorphosis continued until the seascape resembled a scene from a John Piper lithograph, though sadly I don’t think he ever captured this stretch of Welsh coast. This was most certainly the ‘subtle landscape of land and water, a landscape sculpted by hand and time’ as described by Richard Urbanski in his account Walking the Gwent Levels. In the past, a clear calm early April day would have been an ideal time to check over the wooden frames, the putcher ranks, just prior to the start of the summer salmon fishing season. By late April there’d have been hundreds of putchers, willow baskets, full of fish which had been trapped by the previous tide. Last century the fishery declined though and finally ceased in the 1990s, marking the end of millennia of fish- trapping on the estuary. Indeed, those traps we were looking down on are thought to be of medieval origin, at a time when Goldcliff Priory was at its prime. However, the remains of considerably older fish traps (4000 BC) as well as footprints of Mesolithic age have also been discovered in the muds here and elsewhere on the estuary. How many more secrets of the tide might lie out there waiting to be discovered?

The silver shore from Goldcliff

Ancient putcher frame stretching across the foreshore at Goldcliff

Mireland Pill Reen, one of many large drainage ditches across the Levels

View from Hide 1 into the Monks Lagoon, Goldcliff

The Goldcliff Saline Lagoons

On to the famous Goldcliff Lagoons, a birder’s dream and one of Mike’s favourite birding locations. Mike particularly savours his ‘memories of watching the courtship displays of the waders here’ as well as ‘witnessing the birds on migration in autumn’. A birders’ website had previously informed me that its ‘almost always packed with waterfowl and waders throughout the year’ and provides a list of ‘nice birds that can be seen’ including the Little Grebe, Avocet, Dunlin and Little Egret. However, by now, with the rapidly fading light and our limited previous successes earlier in the day, my expectations were modest at best. We scuttled along the path by the Mireland Pill Reen, an impressive reminder of the ‘hand-crafted’ landscape of the Gwent Levels to reach the saline lagoons. Today, sadly, we’d no time to contemplate the wonders of this historic landscape and the feats of generations of engineers who’d claimed and reclaimed these precious agricultural pastures from marine inundation.

Our last stop merely consisted of a short foray into the very spacious and well-constructed hide. Hide 1, The Curlew Hide, overlooks the Monks Lagoon. Given the low light and the considerable distance between us and the birds, it really was bird spotting – the birds, mere spots, were hardly distinguishable against the darkening background. A frustrating wire fence also impaired our view and taking photographs. However, as we were just about able to pick out some waders with long curved bills …may be curlews? Lots and lots of them … but far too far away to photograph. There were also a few other types of waders tucking into the lagoon’s all-you-can-eat buffet, and so I clicked away and hoped at least one photo would be useable! Hopefully, now we’ve found this place, we’ll go back there with more time to spare and better equipment.

Final thoughts

I’d arrived at the wetlands with great expectations. although I’d neither seen nor heard any of the site’s most iconic species, I’ve certainly grown to appreciate the lure of this special place. Perched on the estuary’s edge, sandwiched between space-age industrial and traditional agricultural landscapes, it’s an unlikely place for such a success story. The original vision in establishing the original site has been more than realised. Thanks to massive engineering works, the installation of a sophisticated drainage system, and years of habitat management (overseen by Natural Resources Wales in partnership with RSPB Cymru and Newport City Council), mounds of pulverised fuel ash have been transformed into a rich mosaic of wetland and other habitats. These now support a wealth of plant, invertebrate and bird species as well as weasels, stoats and otters. There are so many groundbreaking achievements to celebrate – wading avocets, elusive bitterns and rare marsh harriers have all bred here for the first time in many years. Indeed, the reserve’s importance was confirmed through its SSSI and National Nature Reserve (NNR) nature conservation status within the last couple of decades. There are challenges, however, even here, as Mike is keen to point out. He, like many of the other birders, would like to see the area treated ‘in a more nature friendly way’ with dogs banned on the reserve. He’s also concerned about the possibility of ‘tidal power wind turbines disrupting the peace and tranquillity.’ There will always be differing ideas about the future of such precious sites, but I’m pleased to note the extensive attempts to bring the local community’s views into the fore, particularly through the Living Levels programme. Also, the achievements which have been accomplished here would not have happened without the help of armies of dedicated volunteers like Mike, who’ve given up so much time and effort to maintain and improve the site. I’m certainly starting to realise the importance of these volunteers – often unsung heroes at so many sites around the estuary.

Evening light across the RSPB Newport Wetlands reserve

Apart from the nature recovery achievements at the site, I’m particularly taken by the accessibility of so much of the wetlands here to the public, although Mike warns of the dangers of treating ‘nature reserves as playgrounds for us humans.’ Young parents with pushchairs, older folks with their packed lunches and binoculars, keen birdwatchers with their giant lenses and others are all there. All sharing and enjoying their bit of ‘wildlife.’ There are lots of special events too to introduce you to the wonders of nature here. Even as I’m writing, there’s a weekend of fun activities ongoing as part of the City Nature Challenge. I agree with Mike that we should value such ‘places for quiet contemplation’ but it’s also important that people can experience, wonder and learn from these sites. Indeed, I hope to go down there myself sometime soon again to attend another workshop. However, this site is only part of the story – there’s much more to explore along the Gwent Levels as the Living Levels’ website informs me. Maybe not for my next walk, but certainly I’ll come back to this extraordinary land/seascape soon.

East Usk lighthouse in the evening light

A few websites of interest

Living Levels / Lefelau Byw website

The Newport Wetland and Goldcliff Loop walk

The Gwent Levels – taken the Historic Landscapes Register

Future-Proofing the Severn Estuary: SEP Secures Nearly £1 Million to Support Long-Term Conservation

The Severn Estuary Partnership (SEP) is delighted to announce the award of £992,285 in funding from the Nature Networks Fund to support the new “Future Proofing the Severn Estuary” project. This significant investment will enhance the protection and resilience of the Severn Estuary’s Marine Protected Areas (MPAs), recognised internationally for their unique habitats and biodiversity.

The Nature Networks Fund is delivered by The National Lottery Heritage Fund in partnership with the Welsh Government and Natural Resources Wales. It aims to support nature recovery and improve the condition and connectivity of protected sites across Wales. SEP’s project builds on three decades of collaborative work across the estuary, and this new initiative will play a vital role in delivering SEP’s vision for a sustainable, thriving Severn Estuary.

Strengthening Biodiversity, Engaging Communities

This funding will enable a wide range of initiatives focused on improving estuary-wide resilience and community engagement. Key actions include:

- Updating the State of the Severn Estuary Report to provide robust, up-to-date data for environmental monitoring and decision-making.

- Supporting the Bird Aware Severn programme, helping to reduce disturbance to sensitive bird populations.

- Managing invasive non-native species and supporting efforts to improve water quality.

- Empowering citizen scientists to help monitor and protect the estuary’s rich biodiversity.

“This is an incredibly exciting opportunity to build on our long-standing work and take concrete steps toward securing the long-term health of the Severn Estuary,” said Alys Morris, SEP Manager. “We look forward to working with our partners and communities to deliver meaningful and lasting change.”

The Severn Estuary spans both England and Wales and is one of the UK’s largest estuaries, home to a vast range of wildlife, landscapes, and communities. As an independent, cross-border initiative hosted by Cardiff University, SEP is uniquely placed to coordinate action across local authorities, government agencies, businesses, and local people.

Dr Rhoda Ballinger, SEP Chair, highlighted the strategic importance of the project:

“This project reflects our continued commitment to collaborative, evidence-led action to support nature recovery and climate adaptation across the estuary. We are also actively seeking additional support to extend these efforts on the English side of the estuary and beyond.”

Andrew White, Director of The National Lottery Heritage Fund in Wales, noted:

“This latest round of awards demonstrates the ambition of the Nature Networks Fund and the importance of connecting people to the natural world on their doorsteps. We are proud to work alongside the Welsh Government and Natural Resources Wales to deliver a more resilient natural environment.”

The “Future Proofing the Severn Estuary” project contributes directly to the ambitions of the Severn Estuary Strategy (2017–2027), particularly in supporting ecosystem-based management, living within environmental limits, and using sound science to inform action.

For updates on this and other projects, follow the Severn Estuary Partnership on social media @SevernEstuary

What a Bore!

Written by Dr Rhoda Ballinger, SEP Chair

I witness a private viewing of our famous Severn Bore at Lower Parting where the Severn splits into two! This month, my article not only shares my experiences from my eventful day, but it also includes some of Stuart Ballard’s memories from his many years of surfing the Tide.

The bore arriving at Lower Parting, Alney Island

Introduction

Since discovering Alney Island on my walk at Gloucester in the autumn, I’d been keen to come back to explore this hidden gem further. Within just a few minutes’ walk from Gloucester Docks, you’re not only stepping onto one of Britain’s largest river islands but you’re also walking into a highly prized nature reserve which includes wet woodlands, marsh and pond habitats. I decided that Lower Parting, at the southern end of the island, would be a perfect place to view the bore. Inspired by the Welsh medieval monk Nennius’ text [The Wonders of Britain], the first written documentation of this natural phenomen, I was convinced that centuries of Severn folk, going as far back as the medieval monks of Gloucester, must have witnessed the bore from this very special vantage point, where the river splits into two.

An extract from Nennius’ medieval text, well over 1200 years old!

| Dau Ri Hafren – The Two Kings of the Severn ‘Two heaped-up wave crests .. Fight each other like rams. One goes against the other, and they clash in turn, and then one withdraws from the other, and they go forth again at each tide. This they have done, from the beginning of the world to this present day.’ |

An extract from Nennius’ medieval text, well over 1200 years old!

A 3* bore offering a ‘moderate’ bore ‘typically up to a metre’ and ‘a good spectacle’ on the 3rd March seemed an opportunity not to be missed. I did understand, though, that preceding meteorological and oceanographic conditions as well as the downstream river flows can modify the size and timing of the bore, so one might turn up and see very little. Anyway, with so few other high starred bores predicted this year, it was worth taking a chance. Geoff very kindly agreed to accompany me, as I’d been slightly perturbed by online discussions of previous walkers’ bovine encounters on the island and, after all, he’d introduced me to the Nennius text.

| What is a tidal bore? These natural phenomena can form as a rising tide forces water to funnel into shallow, sloping coastal inlets (or estuaries). As a tidal wave enters shallow waters, its wave height increases (due to refraction) and the wave travels inland, effectively reversing the river’s flow, sometimes for many miles inland. Bores peak around Spring tides near the vernal and autumnal equinoxes, when the tidal range is greatest. So, this year on the Severn there are only a handful of sizeable bores, even though the tidal river experiences bores twice a day on about 130 days. The speed and height of a bore are influenced by many factors, including wind speed and direction and the rate of flow of freshwater coming downstream. On the Severn, low pressure and south westerly wind are known to increase the size of the wave. |

Given my slight apprehension about a ‘no’ or ‘poor show’, I contacted Stuart Ballard, now part-time River Learning Engagement Officer with the Severn Rivers Trust, a surfing veteran of the bore and one of the famous Muddy Brothers. I vividly remembered Stuart taking me and the SEP team on a most interesting bore safari years ago, and recollected his enthusiastic presentation about bore surfing at a previous Severn Estuary Forum.

In anticipation

Having carefully negotiated the ‘path’ across the waterlogged meadows to the south of Alney Island, we finally arrived at Lower Parting. An empty wooden bench, perfectly positioned on the crest of the riverbank where the river divides into two channels, invited us to the 10:42 performance. Was this really going to be a private viewing? No need to battle through any crowds with over excited children and barking dogs this time. No cattle either (phew). But, goodness, had I got the right time, or even the right day? It was getting ever closer to the predicted time. Bores can even come earlier than predicted – but had we missed it even though we’d arrived 20 minutes early?

As if with no care in the world, the two arms of the river flowed gracefully past us, then merged without even a ripple before continuing downstream to caress the muddy shores of the tree-lined riverbanks beyond. Such a peaceful, rural idyll, with only the occasional long-tailed tit fluttering past and the gentle, distant warbling call of birds, may be skylarks.

Then, an almost eerie stillness and silence before…

The muddy shores as the tip of Lower Parting

The Severn gently flowing downstream before the Bore

The spectacle

A faint swoosh.

Then, the swooshing became louder and louder.

And next, a small flick of white came into sight on the right bank of the river in the far distance.

Within seconds, it was as if an artist’s brush was outlining the riverbank with thicker and thicker strokes, almost dancing along the riverbank, until a white breaker became discernible. The wave rolled on and on, weaving and scouring its way along the bank, crashing into tree trunks and branches. The mallard ducks, which had been gliding so peacefully along the river, initially seemed unperturbed by the approaching wall of white water until, almost engulfed by the spray, they took flight.

Mallard ducks unperturbed by the approaching bore

Mallard ducks taking flight at pace at the fast approaching tidal wave

The bore progressing along the left bank

The show continued. We were suddenly aware of yet another wave meandering its way a little more nonchalantly along the other, inner left bank. This was just like Nennius had described all those centuries ago, although the rams seemed more at peace today than in his description.

And then, the most impressive spectacle of all. The bore broke on the tip of the muddy shore at Lower Parting just in front of us, creating a delightful spray fountain. There followed an unexpected performance from the secondary waves, the whelps. Looking like a series of folds in a velvet gown as they approached, each of these smooth, sleek waves broke gracefully over the previous one in almost slow motion, each drowning more and more of the steep muddy bank below. Very soon the steep bank had been consumed by the frothing waters and there was only swirling chocolate brown, muddy water in front of us.

I hope the following sequence of photos gives you a reasonable impression of this amazing piece of choreography.

The bore’s display at Lower Parting

The aftermath

The show was over, or was it?

The riverbanks and reeds were submerged but still the tide remained in control, flowing steadily upstream and carrying flotillas of debris with it. Pleasingly, given the amount of litter I’ve seen on previous walks, there was relatively little plastic amongst these floating forests. However, driftwood in many shapes and sizes, from crocodile and alligator to otter lookalikes, surged past. Later, I found the following extract from a poem by Duncan Forbes which describes the scene so well:

Shipping the driftwood back upstream

With smells of estuary and reeds,

It fills the channel like a reen

And still the water levels rise

(Source)

By now, the river was nearly at ‘bank full stage’ – and the muddy reed beds of the riverbanks were practically submerged. The water had even started to encroach into the woodland along the banks. In the slightly hazy spring sunshine, it was as if I’d entered the world evoked by Debussy’s impressionistic piano piece Reflets dans l’eau (Reflections in the Water). In and amongst the picturesque reflections, the waters were almost dancing – amazing ripples were forming around bubbling ‘cauldrons’ of water: steady streams of air bubbles were being released, presumably remnants from the bore’s previous disturbance?

And still the waters kept rising.

After all, these are flood meadows, flat pastureland that owes its existence to natural fluvial processes. The West Channel which we were walking along was, I understand, formed by a major flood event centuries ago. As we watched the ancient drainage ditches filling up, I remembered the warnings on the information boards nearby – the river continues to rise for well over an hour after the Bore. Time to beat a hasty retreat. Not so easy though. It was getting increasingly difficult to tread across the heavily trampled, pock-marked sea of sticky mud. Then the inevitable – my walking boot became firmly stuck…I’ll spare you the details, but suffice it to say, I’ve still got a broken fingernail from prizing my boot out, but, at least after a 50° wash cycle, my sock has recovered from its mud bath. What could have been a therapeutic, tactile experience of mud walking, became a logistical nightmare, avoiding the many mighty ziggurats of cow dung strewn across the meadow. At least we didn’t encounter the cattle themselves, although I would quite like to have seen (from a distance) some of the traditional Old Gloucester breed whose milk is used to make the famous Single and Double Gloucester cheeses.

Lower Parting immediately after the Bore

A driftwood ‘crocodile’ floating upstream in the now swollen river

Submerged woodland along the river

Bubbling waters on the edges of the submerged woodland

Over Bridge – the elegant stone arches of Telford’s bridge

Haw Bridge

A pair of geese gliding across one of the many pools of the Ashleworth Ham Reserve

Beyond the Bore

I was so relieved to get to the dry, tarmac path that leads you under Over Bridge, from the top of which I later discovered you get a splendid bird’s eye view of the river without having to negotiate either cattle or mud! The bridge, sometimes known as Telford’s Bridge, is quite special. This elegant bridge was the lowest river crossing on the Severn for over a century until the opening of the Severn Bridge in 1966. It’s main claim to fame though is its design – by Thomas Telford of course. It employs a French ‘cornes de vache’ technique; the horn shaped cut outs on the bridge designed to reduce turbulence and increase water flow at times of flood.

After a quick change of socks and shoes, we warmed up with a hearty lunch at a nearby farm shop café. I was, however, still keen to briefly explore the river up to Haw Bridge, the inland limit of our Severn Estuary Shoreline Management Plan and SEP itself. So, we took a rapid detour by car to sample a few sites upstream before heading home. Haw Bridge itself is somewhat unremarkable, a modern 1960s bridge which replaces a former structure demolished by an empty tanker barge heading downstream. No major disasters on our visit today. By now the river had reverted to flowing downstream and seemed well behaved, even demure, certainly not the ‘naughty adolescent’ as described by Chris Witts. However, despite the somewhat idyllic river scene before us, there was plenty of evidence of previous flooding and high tides – sandbanks piled high along the road in front of the pub, and floating pontoons for the canoeists needing to avoid the steep muddy riverbanks.

Returning towards Maisemore, the normal tidal limit of the Severn, we happened to pass by Ashleworth Ham Reserve, a wonderful wetland which serves as an active floodplain during winter. Although only a remnant of a more extensive wetland landscape, it’s an important bird habitat, with Bewick’s swans and white-fronted geese as regular visitors. On even our brief encounter, we caught a glimpse of various geese, coots, mallards and common pochards.

Our final stop – Maisemore and Upper Parting, at the northern end of Alney Island. The weir at Maisemore is notable as it forms a barrier to the upcoming tides. Stuart thinks that you get one of the best views of the bore here and has even seen footage of the rare Twaite Shad doing their spawning dance at this location. He informs me that it’s quite an odd spectacle seeing the bore ‘smashing against the weir’ before a rebound wave tumbles back downstream against the flow of the incoming tide. Several hours after the bore today, however, it was business as usual with the river flowing downstream. So, another future visit perhaps? Today, after a short walk to Upper Parting it really was time to go home!

Upper Parting with the east and west channels of the Severn

Maisemore weir – the normal tidal limit and upstream limit for the bore

Further bore memories – from Stuart’s bore surfing experiences

I’m so delighted to be able to share a few more memories from Stuart. His tidal surfing adventures have taken him across the world, including to the Benak bore in Borneo where he and other surfers were paraded like gladiators in front of a crowd of no less than 50,000. Why? The river was home to real crocodiles, not like the driftwood ones we’d seen on our bore visit!

I asked Stuart what was so special about the Severn Bore. His reply ‘the great connection with the movements of the solar system as the bore is created by interplay of gravitational forces between the Sun and the Moon…we surf on gravity waves…up the river that flows backwards.’ That sense of connection with something much greater was something we’d also felt even though we’d only passively watched the bore fly by. His most special memory? Well, it had to be ‘surfing along near Newnham with a Harbour Porpoise following me in the incoming tide.’ Or may be ‘surfing past John Powell’s salmon putcher rank at Broadoak when a Grey Mullet leapt out of the roaring tide and landed across my feet in the sunset.’ Stuart was also keen to stress that surfing the bore had given him a ‘connection with the wild nature of place and people’ which ‘had been tangible’. This, he enthusiastically explained, ‘includes the heritage and history of folk living along the river, “the long-village”, as one of the Salmon putcher fishermen called it. ‘Getting to know the Elvermen, the cider makers, surfers and the creative communities has been actually heaven!’ he remarked. Hopefully, I’ll get to know meet some of these stars of the Severn in future walks.

Stuart does admit ‘The tide did take over my life.’ He also stresses how you need to ‘understand just how long the rides can be to understand bore surfing’. He’s proud of his longest single ride of 3.3 miles, and that of his friend, Steve King who ‘holds the record for a standing ride of over 10 miles that took over an hour to complete.’

Surfing the Severn certainly does seem quite an experience. Stuart encourages us to ‘imagine catching one wave that lasts for 20+ minutes rather than the mere seconds one would expect from a wave at the beach’ and ‘how your legs would ache after that!’ He explains ‘this wave would then be carrying you for a journey upriver and inland, past churches, villages, cows, fields, cliffs, under bridges and past pubs. All this with and incredible community of local surfers that has become the ‘Bore Riders Club’, and sometimes hundreds of visiting surfers’. He points out that ‘The Springtime tides can be like a great festival’ and he’s even seen ‘people preparing champagne breakfast on the bank in the Spring sunshine surrounded by apple blossom’. Not Glyndebourne, but clearly an important cultural experience for the Lower Severn communities.

Stuart surfing a cold winter Severn Bore near Arlingham – ‘it’s unusual to have the wave to one’s self!’23/1/2007. Credit Neil Law.

What an atmosphere as surfers flock to the big tides to ’tick off’ their bucket list (21/3/2007) Credit Mark Humpage

Final thoughts

Reflecting on my experiences and on Stuart’s stories which reveal both a passion and an intimate understanding of our tidal river, the Bore is truly one of Britain’s natural treasures. I’m not at all surprised that it was a much celebrated ‘ancient wonder of the British Isles’ in medieval times. Even today, and perhaps especially today, there are few places and times when you can feel so much ‘at one’ with nature and the wider solar system. The bore delivers this and more. With large-scale development proposals and shoreline modifications further downstream does it deserve further protection? Indeed, a recent academic study underscores the need for careful planning in tidal energy development within the Estuary (Source), suggesting that a 1.5 m drop in mean water level could result in a 15 km retreat of the bore.

Whilst the Bore is clearly still culturally significant to the river communities of the Lower Severn, beyond that, perhaps it’s considered a mere quirk. It’s the largest bore in the British Isles but how many people from the cities and towns around our estuary are aware of its existence, never mind have come to see it? Perhaps we need another Magnificent Severn Festival like the one Stuart helped organise back in 2009/10 to help raise its profile. Or even perhaps a new name? After all many of the bores Stuart has surfed elsewhere have names, the ‘Mascaret’, on the Dordogne and Garonne, and the fearsome ‘Pororocca’ on the Amazon. There’s even the infamous ‘Silver Dragon’ on the Qiantang River in China, the world’s largest bore which reaches a staggering 9 metre height.

Beyond considerations of just the bore itself, I’m aware of the need to continue to manage the increasing pressures on the river and its associated flood plains both here and further upstream. It’s great to see the work of the Severn Rivers Trust (which Stuart helped establish), which adopts a catchment-based approach, in line with SEP’s vision, as well as the efforts of more local groups, such as the Friends of Alney Island. With future climate change predictions, we certainly will need a resilient river system and such endeavours need our support.

Finally, I hope you’ve enjoyed reading this article as much as Stuart and I have reflecting on our various experiences. I hope it’s also encouraged you to get out there and watch a bore for real.

A few websites and references

Bore websites:

Boring facts on the Severn Bore

Top Viewing Locations for the Severn Bore

Gloucester Harbour Trustees (2007) Safety Guidance for Surfers, Canoeists, Small Craft and River Bank Users in the Upper Severn Estuary (Source)

The Severn Bore tidal wave – Drone footage and tide timelapse

Surf Simply – Surfing The Severn Bore: The Muddy Brothers and Their Memories

Che, B., Hu, H., Ma, J. and Liang, D., 2024. Hydrodynamic Modelling of Severn Bore and Its Dependence on Ocean Tide and River Discharge. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering, 12(12), p.2319.

Other related topics:

Rediscovering my backyard along the Cardiff Bay Trail

Written by Dr Rhoda Ballinger, SEP Chair

From engineering innovations and maritime heritage to wildlife and national landmarks, I discover some of the current attractions of the Bay and reflects on the urban development process which transformed Tiger Bay into a vibrant waterfront.

Cardiff Barrage from Penarth

Introduction

Having visited a couple of other waterfront developments on my recent Severn walks, I decided it was about time I did a walk along my local waterfront, Cardiff Bay. Having been along this popular section of the Wales Coast Path countless times before, I thought this might be an easy win, given my busy schedule this month. Having taken days to edit my extensive collection of photos of the Bay, I’m not so sure about that now. Anyway, I hope you enjoy reading my article and if you’ve not been to ‘the Bay’ before I hope it will inspire you to come over to Cardiff and sample its many attractions. As with previous articles, I’m delighted that I have had other contributions to add to my ramblings. This month thanks go to David Hall from the Cardiff Bay Harbour Authority and to Nerys Lloyd-Pierce, Chair of the Cardiff Civic Society, for their comments and thoughtful insights.

The barrage and links to the estuary

Under a steel grey sky with only the slightest hint of a watery sun, I embarked on my walk, starting at the Barrage. The sheer scale of this engineering masterpiece never ceases to impress. It certainly needs to be a mighty structure though, impounding both the Ely and Taff, as well as keeping out the estuary’s waters from the 200 ha freshwater lake behind. At just over a kilometre long and with multiple locks, five sluice gates and a fish pass, there’s lots to see. On today’s visit I had the good fortune, or rather I’d planned, to see the barrage operating at both high and low water, so I could appreciate the strength of this structure against the scale of our estuary tides. As you’ll see from my photos it was quite a different seascape at these extremes, even though these weren’t particularly large tides within our tidal cycle.

The barrage was built to create an ‘aesthetically attractive’ waterfront to drive urban regeneration and revive Cardiff’s old dockland areas. It does however, play another key function now, providing some protection from upstream flooding. Each sluice gate can release staggering amounts of water, so if there’s a storm forecast, water can be released into the estuary to make room for further river flows. Even on my visit today, the most westerly sluice gate was open, and water was flowing swiftly out to sea.

Water was also swirling around in the fish pass at the end of barrage. This Denil Pass, which was the largest fish pass in Europe when it was constructed, includes a series of pools and weirs for the migratory fish to negotiate. Looking down at the swirling waters of the fish pass at low water, I’ve always hoped one day I might see some leaping salmon or sea trout, but February is out of season unfortunately. Anyway, I hope the many fishermen who’d set up camp at the end of the outer breakwater of the Barrage would be more fortunate in their catch, particularly given they were sitting out for hours in bitingly cold temperatures

The harbour offshore Cardiff Bay at high water

The harbour offshore Cardiff Bay at low water

The swirling waters of the fish pass at low water

The enormous crocodile bench/ Croc in the Dock, homage to Roald Dahl

Mock white sails brighten up views across the bay

Exotic planting along the landscaped barrage

The barrage promenade

After a most welcome hot drink at the café by the barrage and a quick look at our very own SEP display board, I took the ‘most popular’ stretch of the Wales Coastal Path, along the barrage towards Mermaid Quay. Unlike most previous visits, it was eerily quiet: there was only the occasional dog walker, tourist and cyclist and, apart from a few dishevelled skateboarders, all the play areas were deserted. Against the dark grey forbidding sky the white sails on the barrage really stood out. Although these are supposedly a reminder of Cardiff’s historic sailing tradition, as I looked out across an empty Bay towards a relatively new skyline of apartment blocks and other high-rise buildings, I struggled to imagine the scores of vessels which must have waited outside Cardiff Docks here to load up with South Wales’ ‘gold’: high quality coal. It was also difficult to imagine the scene here immediately prior to the barrage’s construction when you’d have been standing in (rather sinking into!) a sea of undulating mudflats on the edge of the estuary. I do remember well, however, the tortuous debate relating to the demise of these muddy areas before the Cardiff Bay Barrage Act was finally passed: to some these areas were deemed ‘aesthetically unattractive’ but to others they were a haven for wildlife, having been declared a Site of Special Scientific Interest due to their important population of over-wintering birds. No doubt I’ll come back to discuss this further when I visit the Newport Wetlands site, part of the mitigation for the barrage’s impact, in a future walk.

On such a cold day it was difficult contemplating climate change. However, an information board drew my attention to Cardiff County’s first ‘Tiny Forest’ which has been planted to mitigate the effects of climate change. Currently, a somewhat unremarkable patch of saplings on the edge of the barrage, it is hoped this will become a dense native woodland of 1000 trees and will ‘support urban wildlife and reconnect people with nature’. Other attempts to attract wildlife include the landscaping along the barrage which incorporates plant species which can tolerate the demands of this highly exposed coastal environment and also attract key pollinators. Most noticeable was the tall ‘Flagship’ swift tower‘ which plays out quite loud (!) pre-recorded swift calls in an effort to attract swifts, now a red-listed species, to the artificial nest boxes. Penetrating the stillness of the Bay on my visit, I did wonder why the audio was still playing in early February given swifts are summer visitors. On reflection, however, I think the recording is powered by solar energy, which seemingly, even on a drab day in February, still works!

Reminders of Tiger Bay – challenges of urban waterfront regeneration

Descending from the barrage path, there is a short stretch of the Cardiff Bay Trail which my husband describes as the ‘bleak corner,’ where the trail takes you between a derelict old dry dock and the formidable high wire fence of the current port. These remaining pockets of decaying industrial heritage, with their mottled stone walls and rusting infrastructure, are a stark reminder of the immense challenge associated with the sheer scale of redevelopment here – after all nearly 13km of new waterfront were created by the impoundment. Whilst these areas have been recently described in the Welsh news media as ‘wasteland areas … starved of development’, I personally find such sections fascinating photo opportunities, offering rare glimpses of the gritty industrial past of Tiger Bay. However, less appealing were the piles of debris littering the shoreline and floating in some of the more inaccessible water areas – I counted a whole tournament’s worth of footballs and rugby balls bobbing around in a sea of plastic in just one corner of one old dry dock. However, after a succession of intense storms over the last few months, including Storm Bert and Storm Darragh, when I’ve seen whole tree trunks, fridge freezers and more speeding down the Taff, it was hardly surprising to see the volume of material which has collected here. This not only is a formidable clean-up task for the purpose-built Water Witch boats, but also an ecological hazard to shoreline birds. I was particularly saddened to see the poor heron which was camouflaged against the multi-coloured piles of rubbish – if you look carefully you may just see him in the photo below.

Quay walls of the old dry docks

Litter challenges – can you see the heron?

The classic urban waterfront

Continuing along the trail I crossed the ‘Origami-inspired’ bridge, pleasingly colourful on such a dull day. This unusual structure spans the Roath Basin. Looking like a gliding giant red kite, it is quite a contrast in shape and design to the rusting lock gates of the adjacent Roath Basin. Beyond this, the Norwegian Church Arts Centre with its brilliant white wooden cladding, seemed to welcome me to the next section of the waterfront – the spruced up ‘heart’ of Cardiff Bay with its many attractions, including Wales’ national art centre, the Millennium Centre, and The Roald Dahl Plass, a large plaza which hosts public outdoor events. With time no longer on my side, I had to forgo the delicious cakes on offer at the Norwegian Church. However, having many fond memories of family occasions and work events here, I should tell you a little more about this iconic building where Roald Dahl was baptised. Built in 1868, it provided a meeting place for Norwegian seafarers coming ashore from Norwegian ships, berthed in the docks. Interestingly, many of these ships were trading cheap timber from Scandinavian pine forests to service the south Wales coal fields. Having been moved from its original site, it’s now an important arts venue hosting an interesting variety of events and arts exhibitions. I’m certainly looking forward to hearing the Welsh folk string trio, Vri, perform here in a few weeks’ time.

Fortunately, the weather by now was improving so I could indulge myself in a few ‘classic’ photos of the waterfront. As you may appreciate from my photos, there’s an interesting interplay between the old and new here. In the muted afternoon sunshine the old wooden dolphins provided an interesting foreground to the contemporary skyline on the other side of the Bay, and the twenty first century Senedd Building, with its striking wide open glass and slate frontage, even complemented its neighbour, the late nineteenth century Pierhead Building, with its ornate red tiles and clock tower, our Welsh ‘Big Ben!’

As I wanted to get to the wetlands and back to the barrage before dusk, I’d only time for a quick diversion into Roald Dahl Plass to admire the imposing arched bronze roof of the Millennium Centre (or The Armadillo as locals call it), and to appreciate the scale of this plaza. Once the ‘Oval Basin’ and entrance to the old port of Cardiff, it is now completely remodelled with imposing concrete columns. Indeed, it’s attractive modern aesthetic/architecture might be considered the epitome of the ‘superlative maritime city’ envisioned by the Cardiff Bay Development Corporation back in the 1980s. However, I do find it somewhat disappointing that, compared with many other dockland redevelopments, only fragments of the maritime heritage remain here and you do have to look hard to find them. As David notes ‘our maritime history has faded from memory and the city turned its back on the docks and the estuary.’ However, in a discrete corner at the entrance to the Oval Basin I did notice an old water level gauge scored into the stone quayside. These must have been so useful to many a ship’s captain entering the old port. However, standing on the almost deserted concrete pathway, I struggled to contemplate the hustle and bustle of the docks in their heyday. In the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, Cardiff had been the largest coal port in the world – indeed the world’s first ever million-pound deal was struck nearby, in the Coal Exchange. No time to visit that today though, so I continued along the waterfront past a somewhat quieter than usual Mermaid Quay to the old graving docks, now home to Techniquest and some stylish and expensive-looking apartment blocks.

The old lock gates of Roath Basin with the Norwegian Church behind

The iconic wooden dolphins in Cardiff Bay

The Pierhead Building and the Senedd (the seat of Welsh Parliament, Senedd Cymru)

Water level gauge on quayside of the Oval Basin

A walk on the wilder side – Cardiff Bay Wetlands

Even on a relatively quiet day it was quite a contrast entering the Cardiff Bay Wetlands Reserve after seemingly miles of concrete waterfront. Apart from the distant hum of traffic, I really appreciated the relative tranquillity of this 8 hectare site as I wandered along the gravel walkways through the towering reed beds gently swaying in the light breeze. I was particularly enchanted by the elegant swans gracing the wetlands in front of the Windsor Esplanade and was thrilled to catch a few glimpses of other birdlife, including coots, grebes and Canada geese. I wasn’t lucky enough to see the Great Crested Grebes ‘exchanging courtship gifts of aquatic weed’ and ‘the stripe-headed offspring following their parents or even riding on their backs’ as described joyfully by Nerys, but today even the pigeons were keen to put on a display and pose for a photo! What a transformation has taken place over the years since I brought my first group of students to study this site. I must admit to having been rather sceptical about whether it would be possible to create a flourishing freshwater habitat here, particularly when it was replacing a saltmarsh prior to the barrage’s construction. However, thanks to the considerable efforts of the Cardiff Harbour Authority and others who’ve designed, maintained and enhanced this site, this new habitat really does support a rich diversity plant and animal species.

Wetlands in front of the Windsor Esplanade

Pigeons posing on the fence by the walkway

Reed beds in front of the voco St Davids Hotel

Final thoughts

On my return to the barrage, I admired the estuary as the early evening sun and the ebbing tide made for a few last photo opportunities. I agree with David ‘being able to stroll along the Barrage embankment with a large freshwater lake to one side and a huge, ecologically important estuary to the other is a unique experience.’ Tonight, for me the evening sky across the Bay was attractive, but what a beautiful and peaceful vista across the mud flats as the light began to fade. Today these were certainly not ‘unsightly’ mudflats, but, then again, I was only able to appreciate them from the viewing platform afforded by the barrage itself. How ironic. Perhaps the construction of the barrage really ‘was the beginning of when Cardiff learned to love its waterfront again’ as David suggests.

An offshore dolphin emerging from the estuary’s mudflats

On considering the future of this stretch of coast, I was hopeful that there’ll still be an attractive waterfront here in twenty or so years’ time and that we’ll still be able to admire the magic of the shimmering mudflats offshore at low water. There will be challenges, including climate change which particularly concerns Nerys, but hopefully environmental projects, such as the Tiny Forest, will flourish and help mitigate some impacts. In terms of Cardiff Bay, I’d tend to agree with David’s view that ‘the greatest challenge’ here ‘relates to balancing the demand for future development, whilst ensuring that it remains a peaceful and attractive place to visit.’ Given the number of new development proposals, even including re-redevelopment schemes at Atlantic Wharf, these will all have to be very carefully managed.

As I finished my walk, tired and rather peckish, I reflected on my day and on the wider lessons learnt from the urban development process here. All seems good now, but that’s only thanks to the intense scrutiny of potential environmental impacts in the 80s and 90s, the considerable expenditure to address these impacts and the ongoing efforts of the Cardiff Harbour Bay Authority. Questions remain over the compensation for lost environmental interest associated with the demise of the mudflats. Are there lessons here for other large scale estuary developments, I wonder?

Sunset across Cardiff Bay

A few more interesting websites on Cardiff Bay and walks for you to try

Cardiff Bay – Cardiff Harbour Authority website

More than the Portishead blues – shore delights at Portishead

Written by Dr Rhoda Ballinger, SEP Chair

I discover more hidden treasures along our Severn shores and sample sections of the coast from Redcliffe Bay (Somerset) to Portishead Marina. Offering a brief insight into the maritime and natural history of this coast, I recount my observations from my very chilly visit early in the New Year.

Black-headed gulls with their winter plumage circling in front of Battery Point Lighthouse

Introduction

On one of the coldest but clearest of days early in January, I ventured out with Geoff, my husband, to the explore the coast from Redcliffe Bay (Somerset) to Portishead Marina, taking in sections of the North Somerset Tidal Trail and the Gordano Round. Ever since sailing around the Upper Estuary on the Waverley last summer, I’d been intrigued to explore this stretch of coast further – I’d not only been surprised by the grandeur of the former National Nautical School from offshore but also the unexpected swathes of natural shoreline so close to the docks downstream of the Avon. Given the extreme temperatures and the limited hours of daylight, it was more of a Saga tour than an exhilarating walk, hopping in and out of our car to sample the highlights and then try to get warm. We even took the advice from the online Bristol Barkers’ walk and tested the delights of the Windmill Inn for lunch – to be recommended!

Supplementing my impressions from our brief visit, I’m delighted to share with you more informed views from a couple of Portishead town councillors. Councillor Jenie Eastman (councillor for West Ward including Redcliffe Bay) has lived in Portishead for nearly 30 years, and like me, is a proud geographer with a passion for exploring the balance between the physical and human worlds. Councillor David Gunnell (councillor for North Ward including the Lake Grounds area) is an even longer-term resident of Portishead, who, as a retired clinician and academic, is passionate about mental wellbeing as well as being a volunteer on a local nature reserve.

Safety first: Lighthouses along the Portishead shore

One of the main attractions of the Portishead shore is the view across the estuary towards Denny Island/Ynys Denny, just three miles offshore. On such a calm day this tiny uninhabited island appeared little more than a dark hump emerging out of the still estuary waters at high tide, but as the tides receded further the full extent of the offshore sandbanks and muddy shores were revealed – this reminded us of more serious, safety matters and the need for navigational aids along this potentially treacherous stretch of coast. Brunel’s great transatlantic passenger ship, the SS Great Western ran aground off Nore Point in 1838 and this was the impetus for the construction of Black Nore Lighthouse in 1894. Inspired by this, we made our way along the muddy but still slightly frosty path to the lighthouse. Gleaming in the winter sunshine and casting long dark shadows across the beach below, it was easy to see why this slightly quirky Grade II listed ‘pepper pot’ lighthouse is such an inspiration for local artists. Its white cast iron tower sits atop a skirt of six metallic legs, looking more like a Wallace and Gromit model spaceship ora ‘stilted steam-punk iron torch,’ as Matt Gilbert describes it in his poem ‘At Black Nore Lighthouse,’ than a serious piece of engineering. On such a calm day, however, this solitary sentinel exuded a calm authority and sense of comfort – after all, it had watched over this stretch of waters for well over a hundred years, until its decommissioning in 2010.

Geoff walking along the coastal path at Black Nore Lighthouse

Not surprisingly given the coast’s proximity to the entrance of Royal Portbury Dock, there’s another lighthouse just upstream on the tip of Portishead Point, as mariners refer to it, or Battery Point, if you’re a local. Continuing our lighthouse crawl, we approached this 9-metre-high structure from the coast path and were immediately aware of its somewhat more unusual design than its cousin down the coast – with its black metal pyramid tower resting on a rather grey and weathered square concrete base, it looked more like a miner’s lamp than a navigational aid. Lying silent and still, it was also difficult to imagine this relatively small structure providing sufficient warning for shipping. This automatic navigational light, however, is still fully functional, being maintained by the Bristol Port Company and remains critical to navigation. Just as well, given that large ships pass closer to land here than anywhere else along the entire UK coastline! A local campaign has also ensured that the lighthouse’s original two-tonne fog bell, which was removed due to structural issues, is not forgotten. It’s now been re-erected near the town’s centre as a reminder of Portishead’s maritime past.

A distant view of Denny Island, Wales – an inspiration for Melania Trumps’ milliner?!

A close-up of Black Nore Lighthouse

Battery Point Lighthouse