Tracing the Tides of Coastal Management Across the Gwent Levels

Rhoda takes an unexpected visit to the Wentlooge Levels uncovering remarkable stories of how people have lived, worked, and shaped these rich cultural and ecological landscapes.

Photo: The mighty embankment along the Wentlooge Levels

Well, things didn’t go quite to plan. As we ground to a halt on the M4, it became clear that our walk around Lydney Harbour wasn’t to be, especially, once our SatNav had announced a two-hour delay. With no contingency arrangements in place, we pulled into the nearest café, feeling a little like eager contestants in a travel race! The soundtrack was an unlikely mix of bleating goats and clucking hens—no surprise, since we’d inadvertently landed at the Walnut Tree Farm Park. Tempting though a ‘fun-filled day out with farmyard animals’ sounded, we decided to pass. Wrestling with a patchy mobile phone signal, we eventually pieced together that we weren’t too far from St Brides Wentlooge. So, a new plan unfolded – why not explore the coast west of the Usk and take in some of the villages of the Levels as well? After all, centuries ago these parts of the Severn certainly hadn’t been prepared for what was to happen there either ….

Photo: … the need for a sudden change of plan

The Villages of the Gwent Levels – discovering some ‘evidence’ for the 1607 flood

Photo: The idyllic setting of St Bridgets church at St Brides Wentlooge

Approaching the peaceful, sleepy village of St Brides on a golden autumn day was pure delight. The hedgerows were heavy with berries, and the long slender drainage ditches, the reens that cut across the low-lying pastureland, shimmered in the sunlight. After a brief SatNav mishap (it clearly wasn’t our day for car travel!), we finally discovered the handsome stone church of St Bridgets. Once the heart of the village, it now lies tucked away among a cluster of small — and some rather exclusive — modern housing developments, typical of many of the rural communities on the Levels. The extensive modern paving that fronts many of the houses suggests that some residents may be only dimly aware of the village’s history of flooding, or of the vital role played by the reens, which now appear more like ornamental garden features rather than essential drainage ditches.

Photo: Recent development and paving alongside reedy drainage ditches at St Brides

Peering into the whitewashed porch of the church, we were immediately reminded of the most devastating flood ever to strike this area — a disaster dating back to the early 17th century. Carved into a weathered stone plaque, we could just make out the words: “The Great Flood of 20 Januarie, 10 in the morning, 1606.” This was no hoax or cryptic clue from an episode of Celebrity Traitors, but a genuine fragment of history. The date, of course, was puzzling — a relic from the time before Britain abandoned the old Julian (Roman) calendar for the Gregorian one in 1752. Yet despite the archaic spelling and the centuries that had worn the stone, the inscription felt startlingly alive. Standing there, tracing the deep grooves with our eyes, we could almost sense the fear and grief of those villagers who had deemed it essential to mark such a catastrophic event.

Photo: The plaque in the porch of St Bridgets commemorating the Great Flood of 1606!

After a couple of brief distractions — gathering a few handfuls of sloe berries from the church car park and chatting with a delightful former resident of the village, whose entire family was buried in the graveyard — we set off to collect more ‘evidence’ of the Great Flood of 1607, visiting the neighbouring villages and churches that still bear traces of its memory, as I was aware that extensive areas of the Levels had been devastated by this event.

Photo: A few of the sloe berries which are now contributing to the production of a special Severn Sloe Gin!

After a bit of rummaging around, we eventually found commemorative plaques, markers, and other signs in and around the churches at three other villages, Redwick, Peterstone, and Nash — as shown in the photo montage below. All, however, was not quite as it seemed.

Photo: ‘Evidence’ at St Thomas (Redwick), Peterstone and St Marys (Nash) (left to right)

Later, after contacting Rose Hewlett — who has been researching the flood in this area and across the estuary for her PhD, delving into countless lesser-known sources such as land drainage and sea defence records — I discovered that some of our evidence was somewhat misleading. The floodwaters had indeed reached an extraordinary height, as shown in the famous woodcut from a contemporary London pamphlet, reproduced below, though that dramatic image was clearly intended to boost sales. The mark on the outside of the church porch at Redwick, however, turned out to be somewhat misleading. According to experts, the true flood level is recorded on the exterior wall of the chancel …. which we eventually located and which I am pointing out in the photograph below.

Photo: A graphic depiction of the Great Flood from a London pamphlet (chapbook) of the time

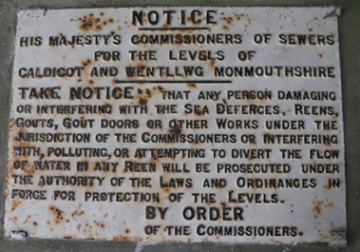

As I’m around 1.8 metres tall, you can roughly gauge the height of the waters for yourself. And this was no calm, glassy lake: accounts from the time describe the floodwaters surging across the Levels “as fast as a greyhound” — roughly about 45 miles (72 Kilometres) per hour. Not only that, but Rose’s research also suggests that the flood was driven by ferocious winds, as a severe storm swept across the small villages and farmland. Despite primitive flood warnings, tolling bells from local churches (not automatically generated texts or phone calls), the communities weren’t prepared for an event of such magnitude. People were stuck up trees for three days (in January!) while others sought refuge on their rooftops. It’s impossible to know exactly how many lives were lost, but contemporary pamphlets estimate between 500 and 2,000 deaths. Great numbers of livestock perished too, including four hundred sheep further north near Lydney. And because the disaster struck in midwinter, many winter crops were ruined by the saltwater. Small wonder, then, that the London pamphlet Lamentable Newes out of Monmouthshire in Wales described it as “the wonderfull and most fearefull accidents of the great outflowing of waters.” It’s also unsurprising that we later found a more modern plaque threatening prosecution for anyone damaging the flood defences — a relic of the days when the ominously named Commissioners of Sewers held authority. More on them later.

Photo: The true height of the Redwick flood!

Photo: Historic prosecution threats at Redwick!

Exploring the Wentlooge coast – shore contrasts

Although by now I’d accumulated a fair amount of evidence about the Great Flood, the weather was still on our side, so we ventured down to the estuary to explore the modern shore. Walking along the Wales Coast Path from the now sadly derelict Lighthouse Inn, I was surprised to see how many other walkers were also out enjoying the rare autumn sunshine, the sweeping views, and the relative peace this path affords.

From our vantage point atop the prominent St Brides seawall, we could truly appreciate the vast scale of the estuary and the surrounding Levels, as well as contemplate changes in the landscape since that catastrophic event over four hundred years ago. In one direction, perhaps the landscape hasn’t changed that much – idyllic countryside stretches out seemingly for miles — cattle grazing on green pastures, still criss-crossed by the ancient drainage ditches that have kept this land habitable and productive for centuries. There’s even a fascinating old vocabulary tied to this landscape: sewers, gouts, stanks and reens — all terms related to drainage, and all, incidentally, valid Scrabble words!

To the east, towards Newport, however, it’s a different story with a forest of pylons and an industrial skyline dominating the horizon. We watched as a cargo ship, the Arklow Resolve, glided effortlessly past the RSPB wetlands reserve on its way to Newport Docks, dwarfing the modest East Usk Lighthouse we’d visited just a few months earlier. This was a vivid reminder that, even in the post-industrial age, our estuary remains a vital artery of trade and the surrounding shores are vital assets to our regional economy. Indeed, Newport’s port, supported by excellent road and rail connections, still handles around £1 billion of UK commerce each year,– that’s a staggering £2.7 million a day!

Photo: The rural Levels stretch for miles inland of the current coast

Photo: Industrial landscapes along the lower Usk with the surface water patterns hinting at the ancient field patterns in the foreground, seaward of the sea wall

Photo: The cargo ship, the Arklow Resolve, approaching Newport

As we looked across towards the old West Usk Lighthouse, the past and present seemed to merge. Lofty wind turbines rose proudly above the pastureland, while industrial chimneys stood in sharp contrast to the rolling, wooded hills beyond. As I stood taking in the scene, it was easy to appreciate how history has shaped the character of this wide coastal plain—layered, complex, and ever evolving, with significant solar power development proposals being mooted over some of the Levels. Even the West Usk Lighthouse isn’t quite what it first appears. Once a vital navigation aid, it originally stood on a small island near the shore, marking the entrance to the Usk river channel and guiding ships toward the docks from 1821 for more than a century. Today, with its fresh whitewashed exterior, it’s taken on a very different role. Now serving as an intimate venue for weddings and special events, it’s also no longer isolated at sea, sitting firmly on the mainland, protected by imposing banks of boulders, ‘riprap’ as the experts call it.

Photo: The West Usk Lighthouse and surroundings

Elsewhere along this coast, it’s impossible not to be struck by the sheer scale of the sea defences which stretch for kilometres in both directions. The Gwent Levels sit only about seven metres above mean sea level, and, as I’m sure you’ll be aware, the tidal range of the Severn reaches an astonishing fourteen metres. So, robust protection has long been essential. In fact, storm defences have been in place in one form or another since Roman times. And today, these defences are certainly not half-measures. As we made our way back towards the Lighthouse Inn and beyond, we were struck by the multiple layers of protection, illustrated in the following photos. The current seawall is an impressive and sizeable grassy embankment. Then, seaward of that, a broad strip of riprap armours the edge of a grassy terrace. Beyond even that, occasional double groyne structures reach out into the estuary, and further beyond that again nature’s defence – wide, muddy intertidal areas. Their surface—rippled, folded, and oddly brain-like—glimmered in the afternoon light. Further west, more obvious concrete engineered structures protect the shore, leading eventually to the Peterstone Gout or Great Gout,—a tidal flap regulating drainage into the estuary. Well-known among birdwatchers for the wildlife it attracts, it also plays a vital role in the ingenious drainage system of the Levels. An outlet here was likely first constructed by the Romans around 1,800 years ago, and remarkably, this same point still serves as the main drainage outlet for the entire Wentlooge Level, some 34 square kilometres of fertile farmland.

Photo: Double defences protecting the Wentlooge Levels

Photo: Natural defences – cerebriform, brain-like, muddy shores, helping to attenuate wave energy

Photo: The Peterstone Gout, which regulates water drainage into the estuary

As we headed back along the coast path, I couldn’t help feeling a flicker of concern at the obvious signs of recent storms. Massive, smoothly polished tree trunks lay scattered across the marshy terrace, now dotted with pools and scarred by indentations. Some trunks had even been tossed—like discarded matchsticks—well above the terrace, now resting partway up the highest embankment, that final barrier protecting the fields beyond. Oblivious of this, the cattle were contentedly chewing the cud on the top of the bank, only a few metres above!

Photo: A tree trunk with antler-like branches lies across the marshy terrace

Photo: Evidence of previous storm activity

Photo: Peacefully chewing the cud, above a significant strandline

Reflections and conclusions

It turned into a very different day from the one I’d planned—unexpected, but more fascinating because of it. On the journey home, I found myself wanting to dig deeper into the stories behind the sea defences and drainage systems that have shaped this remarkable ancient coastline. The Great Flood of 1607 remains one of Britain’s most devastating natural disasters, still etched into our collective memory. And as I soon discovered—thanks in large part to Rose’s research and the insights of landscape historian Stephen Rippon—the history of this place is even more compelling than I’d imagined.

What surprised me most was just how much has been recorded about the evolution of this hand-crafted, distinctive coastal plain, a landscape now recognised as being of outstanding historical and cultural importance internationally. Unlike many other coastal areas that were extensively drained and converted from saltmarsh to farmland, this stretch of coast still preserves a wealth of archaeological evidence—from settlement patterns to historic field layouts—including the very features I’d been admiring from the St Brides seawall.

By the time the Great Flood struck in 1607, this coastline already had a long legacy of ‘shoreline management’: from Roman interventions and the work of medieval monastic communities to the establishment of Henry VIII’s ‘Act of Sewers’ in 1531. That law created Courts of Sewers and Commissioners—local landowners tasked with managing drainage infrastructure, inspecting seawalls and gouts, and ensuring that maintenance was carried out. In 1607, the Right Honourable Lord Herbert and Sir Walter Montagu were among those overseeing this system along the Gwent coast. What is particularly striking is how these commissioners coordinated the evacuation and relief efforts immediately after the flood—organising food distribution and implementing levies on local parishioners who benefitted from the sea defences. What might, at first glance, appear to have been a primitive system—as suggested by the famous woodcut—is revealed to have been far more organised. In fact, some elements of the management framework in place during the Great Flood can be seen as a direct ancestor of today’s Internal Drainage Boards, now incorporated within Natural Resources Wales.

You’re probably wondering whether something like the Great Flood of 1607 could happen again? History certainly suggests that the sea along this coast has never been a quiet neighbour. Rose suggests that the local people were used to repairing the occasional small breach in the seawall after severe storms. Records from 1097 tell of the waters bursting over their banks in Monmouthshire and Glamorganshire, drowning people and livestock near the Usk at Newport. Then, in 1116, devastating Christmas floods swept through the region, wiping out cattle and causing famine. When disaster struck again in 1607, London pamphleteers framed it as divine punishment—a heavenly reckoning aimed at the local population.

Today, well, we’re not entirely sure of the event’s origin, although from Rose’s study of eye-witness accounts, including from reputable local church people, it seems there was a lengthy storm accompanied by strong winds. The event also seems to have coincided with an extra big spring tide. However, others point to the possibility of the flooding having been triggered by a tsunami, although there seems limited evidence for this. I’ve shared a few references below if you’re curious to explore further.

Looking ahead, we’d be unwise to shrink from the reality of rising sea levels and increasingly powerful storms—those stranded tree trunks lodged high on the embankment are sobering enough. Still, there is reassurance in knowing that a “Hold the Line” policy currently protects this part of the Severn Estuary, meaning today’s sea defences are intended to stay broadly where they are for the foreseeable future here (Severn Estuary Shoreline Management Plan – Wentlooge ). However, the shoreline management plan does note that the existing defences will ‘come to the end of their serviceable life in this epoch’ (2025 to 2055)’ and will need replacing, presumably at some significant cost. The Plan suggests creating new intertidal habitats to both improve defences and compensate for habitat loss from coastal squeeze around the estuary. By the end of the century, this coastline could look very different indeed.

What won’t change is the significance of this place. It remains a unique and deeply valued coastal landscape, rich in history and identity, as well as in ecological importance. Any proposals to alter it must face thorough scrutiny. After all, as I’ve found out from researching this article. we’re just one chapter in a much longer story of people living with and, indeed sometimes against, the Severn Estuary. And it’s up to us to make sure the legacy we leave behind is one that future generations can look back on with pride.

Photo: The rich muds at Peterstone Wentlooge

Further information

History of the Levels and its drainage system

Gwent Levels Historic Landscape of Outstanding Historic Interest in Wales – a brief description of the key aspects which contribute to this areas’ historic character.

The Origins of the Gwent Levels drainage system in the medieval period – an online presentation by Professor Stephen Rippon

A history of the drainage of The Gwent Levels

Beyond the seawall – a guide to exploring the intertidal zone along the Gwent Levels

Levels lingo – a guide to the drainage and other local terms used on the Gwent Levels

The Great Flood of 1607

The day the sea came in – 1607 on the Gwent Levels – a children’s story based on Rose’s research

Catastrophic Wave Erosion, Bristol Channel, United Kingdom: Impact of Tsunami?

The Bristol Channel floods of 1607 – reconstruction and analysis

Severn Estuary Partnership

Severn Estuary Partnership