Tracing the Tides of Coastal Management Across the Gwent Levels

Rhoda takes an unexpected visit to the Wentlooge Levels uncovering remarkable stories of how people have lived, worked, and shaped these rich cultural and ecological landscapes.

Photo: The mighty embankment along the Wentlooge Levels

Well, things didn’t go quite to plan. As we ground to a halt on the M4, it became clear that our walk around Lydney Harbour wasn’t to be, especially, once our SatNav had announced a two-hour delay. With no contingency arrangements in place, we pulled into the nearest café, feeling a little like eager contestants in a travel race! The soundtrack was an unlikely mix of bleating goats and clucking hens—no surprise, since we’d inadvertently landed at the Walnut Tree Farm Park. Tempting though a ‘fun-filled day out with farmyard animals’ sounded, we decided to pass. Wrestling with a patchy mobile phone signal, we eventually pieced together that we weren’t too far from St Brides Wentlooge. So, a new plan unfolded – why not explore the coast west of the Usk and take in some of the villages of the Levels as well? After all, centuries ago these parts of the Severn certainly hadn’t been prepared for what was to happen there either ….

Photo: … the need for a sudden change of plan

The Villages of the Gwent Levels – discovering some ‘evidence’ for the 1607 flood

Photo: The idyllic setting of St Bridgets church at St Brides Wentlooge

Approaching the peaceful, sleepy village of St Brides on a golden autumn day was pure delight. The hedgerows were heavy with berries, and the long slender drainage ditches, the reens that cut across the low-lying pastureland, shimmered in the sunlight. After a brief SatNav mishap (it clearly wasn’t our day for car travel!), we finally discovered the handsome stone church of St Bridgets. Once the heart of the village, it now lies tucked away among a cluster of small — and some rather exclusive — modern housing developments, typical of many of the rural communities on the Levels. The extensive modern paving that fronts many of the houses suggests that some residents may be only dimly aware of the village’s history of flooding, or of the vital role played by the reens, which now appear more like ornamental garden features rather than essential drainage ditches.

Photo: Recent development and paving alongside reedy drainage ditches at St Brides

Peering into the whitewashed porch of the church, we were immediately reminded of the most devastating flood ever to strike this area — a disaster dating back to the early 17th century. Carved into a weathered stone plaque, we could just make out the words: “The Great Flood of 20 Januarie, 10 in the morning, 1606.” This was no hoax or cryptic clue from an episode of Celebrity Traitors, but a genuine fragment of history. The date, of course, was puzzling — a relic from the time before Britain abandoned the old Julian (Roman) calendar for the Gregorian one in 1752. Yet despite the archaic spelling and the centuries that had worn the stone, the inscription felt startlingly alive. Standing there, tracing the deep grooves with our eyes, we could almost sense the fear and grief of those villagers who had deemed it essential to mark such a catastrophic event.

Photo: The plaque in the porch of St Bridgets commemorating the Great Flood of 1606!

After a couple of brief distractions — gathering a few handfuls of sloe berries from the church car park and chatting with a delightful former resident of the village, whose entire family was buried in the graveyard — we set off to collect more ‘evidence’ of the Great Flood of 1607, visiting the neighbouring villages and churches that still bear traces of its memory, as I was aware that extensive areas of the Levels had been devastated by this event.

Photo: A few of the sloe berries which are now contributing to the production of a special Severn Sloe Gin!

After a bit of rummaging around, we eventually found commemorative plaques, markers, and other signs in and around the churches at three other villages, Redwick, Peterstone, and Nash — as shown in the photo montage below. All, however, was not quite as it seemed.

Photo: ‘Evidence’ at St Thomas (Redwick), Peterstone and St Marys (Nash) (left to right)

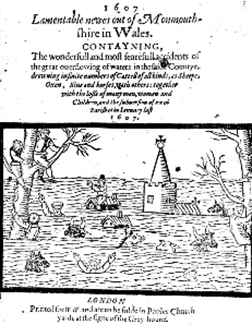

Later, after contacting Rose Hewlett — who has been researching the flood in this area and across the estuary for her PhD, delving into countless lesser-known sources such as land drainage and sea defence records — I discovered that some of our evidence was somewhat misleading. The floodwaters had indeed reached an extraordinary height, as shown in the famous woodcut from a contemporary London pamphlet, reproduced below, though that dramatic image was clearly intended to boost sales. The mark on the outside of the church porch at Redwick, however, turned out to be somewhat misleading. According to experts, the true flood level is recorded on the exterior wall of the chancel …. which we eventually located and which I am pointing out in the photograph below.

Photo: A graphic depiction of the Great Flood from a London pamphlet (chapbook) of the time

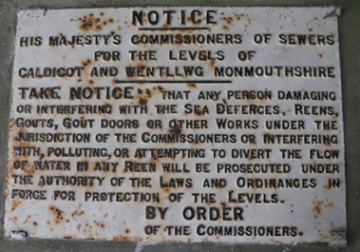

As I’m around 1.8 metres tall, you can roughly gauge the height of the waters for yourself. And this was no calm, glassy lake: accounts from the time describe the floodwaters surging across the Levels “as fast as a greyhound” — roughly about 45 miles (72 Kilometres) per hour. Not only that, but Rose’s research also suggests that the flood was driven by ferocious winds, as a severe storm swept across the small villages and farmland. Despite primitive flood warnings, tolling bells from local churches (not automatically generated texts or phone calls), the communities weren’t prepared for an event of such magnitude. People were stuck up trees for three days (in January!) while others sought refuge on their rooftops. It’s impossible to know exactly how many lives were lost, but contemporary pamphlets estimate between 500 and 2,000 deaths. Great numbers of livestock perished too, including four hundred sheep further north near Lydney. And because the disaster struck in midwinter, many winter crops were ruined by the saltwater. Small wonder, then, that the London pamphlet Lamentable Newes out of Monmouthshire in Wales described it as “the wonderfull and most fearefull accidents of the great outflowing of waters.” It’s also unsurprising that we later found a more modern plaque threatening prosecution for anyone damaging the flood defences — a relic of the days when the ominously named Commissioners of Sewers held authority. More on them later.

Photo: The true height of the Redwick flood!

Photo: Historic prosecution threats at Redwick!

Exploring the Wentlooge coast – shore contrasts

Although by now I’d accumulated a fair amount of evidence about the Great Flood, the weather was still on our side, so we ventured down to the estuary to explore the modern shore. Walking along the Wales Coast Path from the now sadly derelict Lighthouse Inn, I was surprised to see how many other walkers were also out enjoying the rare autumn sunshine, the sweeping views, and the relative peace this path affords.

From our vantage point atop the prominent St Brides seawall, we could truly appreciate the vast scale of the estuary and the surrounding Levels, as well as contemplate changes in the landscape since that catastrophic event over four hundred years ago. In one direction, perhaps the landscape hasn’t changed that much – idyllic countryside stretches out seemingly for miles — cattle grazing on green pastures, still criss-crossed by the ancient drainage ditches that have kept this land habitable and productive for centuries. There’s even a fascinating old vocabulary tied to this landscape: sewers, gouts, stanks and reens — all terms related to drainage, and all, incidentally, valid Scrabble words!

To the east, towards Newport, however, it’s a different story with a forest of pylons and an industrial skyline dominating the horizon. We watched as a cargo ship, the Arklow Resolve, glided effortlessly past the RSPB wetlands reserve on its way to Newport Docks, dwarfing the modest East Usk Lighthouse we’d visited just a few months earlier. This was a vivid reminder that, even in the post-industrial age, our estuary remains a vital artery of trade and the surrounding shores are vital assets to our regional economy. Indeed, Newport’s port, supported by excellent road and rail connections, still handles around £1 billion of UK commerce each year,– that’s a staggering £2.7 million a day!

Photo: The rural Levels stretch for miles inland of the current coast

Photo: Industrial landscapes along the lower Usk with the surface water patterns hinting at the ancient field patterns in the foreground, seaward of the sea wall

Photo: The cargo ship, the Arklow Resolve, approaching Newport

As we looked across towards the old West Usk Lighthouse, the past and present seemed to merge. Lofty wind turbines rose proudly above the pastureland, while industrial chimneys stood in sharp contrast to the rolling, wooded hills beyond. As I stood taking in the scene, it was easy to appreciate how history has shaped the character of this wide coastal plain—layered, complex, and ever evolving, with significant solar power development proposals being mooted over some of the Levels. Even the West Usk Lighthouse isn’t quite what it first appears. Once a vital navigation aid, it originally stood on a small island near the shore, marking the entrance to the Usk river channel and guiding ships toward the docks from 1821 for more than a century. Today, with its fresh whitewashed exterior, it’s taken on a very different role. Now serving as an intimate venue for weddings and special events, it’s also no longer isolated at sea, sitting firmly on the mainland, protected by imposing banks of boulders, ‘riprap’ as the experts call it.

Photo: The West Usk Lighthouse and surroundings

Elsewhere along this coast, it’s impossible not to be struck by the sheer scale of the sea defences which stretch for kilometres in both directions. The Gwent Levels sit only about seven metres above mean sea level, and, as I’m sure you’ll be aware, the tidal range of the Severn reaches an astonishing fourteen metres. So, robust protection has long been essential. In fact, storm defences have been in place in one form or another since Roman times. And today, these defences are certainly not half-measures. As we made our way back towards the Lighthouse Inn and beyond, we were struck by the multiple layers of protection, illustrated in the following photos. The current seawall is an impressive and sizeable grassy embankment. Then, seaward of that, a broad strip of riprap armours the edge of a grassy terrace. Beyond even that, occasional double groyne structures reach out into the estuary, and further beyond that again nature’s defence – wide, muddy intertidal areas. Their surface—rippled, folded, and oddly brain-like—glimmered in the afternoon light. Further west, more obvious concrete engineered structures protect the shore, leading eventually to the Peterstone Gout or Great Gout,—a tidal flap regulating drainage into the estuary. Well-known among birdwatchers for the wildlife it attracts, it also plays a vital role in the ingenious drainage system of the Levels. An outlet here was likely first constructed by the Romans around 1,800 years ago, and remarkably, this same point still serves as the main drainage outlet for the entire Wentlooge Level, some 34 square kilometres of fertile farmland.

Photo: Double defences protecting the Wentlooge Levels

Photo: Natural defences – cerebriform, brain-like, muddy shores, helping to attenuate wave energy

Photo: The Peterstone Gout, which regulates water drainage into the estuary

As we headed back along the coast path, I couldn’t help feeling a flicker of concern at the obvious signs of recent storms. Massive, smoothly polished tree trunks lay scattered across the marshy terrace, now dotted with pools and scarred by indentations. Some trunks had even been tossed—like discarded matchsticks—well above the terrace, now resting partway up the highest embankment, that final barrier protecting the fields beyond. Oblivious of this, the cattle were contentedly chewing the cud on the top of the bank, only a few metres above!

Photo: A tree trunk with antler-like branches lies across the marshy terrace

Photo: Evidence of previous storm activity

Photo: Peacefully chewing the cud, above a significant strandline

Reflections and conclusions

It turned into a very different day from the one I’d planned—unexpected, but more fascinating because of it. On the journey home, I found myself wanting to dig deeper into the stories behind the sea defences and drainage systems that have shaped this remarkable ancient coastline. The Great Flood of 1607 remains one of Britain’s most devastating natural disasters, still etched into our collective memory. And as I soon discovered—thanks in large part to Rose’s research and the insights of landscape historian Stephen Rippon—the history of this place is even more compelling than I’d imagined.

What surprised me most was just how much has been recorded about the evolution of this hand-crafted, distinctive coastal plain, a landscape now recognised as being of outstanding historical and cultural importance internationally. Unlike many other coastal areas that were extensively drained and converted from saltmarsh to farmland, this stretch of coast still preserves a wealth of archaeological evidence—from settlement patterns to historic field layouts—including the very features I’d been admiring from the St Brides seawall.

By the time the Great Flood struck in 1607, this coastline already had a long legacy of ‘shoreline management’: from Roman interventions and the work of medieval monastic communities to the establishment of Henry VIII’s ‘Act of Sewers’ in 1531. That law created Courts of Sewers and Commissioners—local landowners tasked with managing drainage infrastructure, inspecting seawalls and gouts, and ensuring that maintenance was carried out. In 1607, the Right Honourable Lord Herbert and Sir Walter Montagu were among those overseeing this system along the Gwent coast. What is particularly striking is how these commissioners coordinated the evacuation and relief efforts immediately after the flood—organising food distribution and implementing levies on local parishioners who benefitted from the sea defences. What might, at first glance, appear to have been a primitive system—as suggested by the famous woodcut—is revealed to have been far more organised. In fact, some elements of the management framework in place during the Great Flood can be seen as a direct ancestor of today’s Internal Drainage Boards, now incorporated within Natural Resources Wales.

You’re probably wondering whether something like the Great Flood of 1607 could happen again? History certainly suggests that the sea along this coast has never been a quiet neighbour. Rose suggests that the local people were used to repairing the occasional small breach in the seawall after severe storms. Records from 1097 tell of the waters bursting over their banks in Monmouthshire and Glamorganshire, drowning people and livestock near the Usk at Newport. Then, in 1116, devastating Christmas floods swept through the region, wiping out cattle and causing famine. When disaster struck again in 1607, London pamphleteers framed it as divine punishment—a heavenly reckoning aimed at the local population.

Today, well, we’re not entirely sure of the event’s origin, although from Rose’s study of eye-witness accounts, including from reputable local church people, it seems there was a lengthy storm accompanied by strong winds. The event also seems to have coincided with an extra big spring tide. However, others point to the possibility of the flooding having been triggered by a tsunami, although there seems limited evidence for this. I’ve shared a few references below if you’re curious to explore further.

Looking ahead, we’d be unwise to shrink from the reality of rising sea levels and increasingly powerful storms—those stranded tree trunks lodged high on the embankment are sobering enough. Still, there is reassurance in knowing that a “Hold the Line” policy currently protects this part of the Severn Estuary, meaning today’s sea defences are intended to stay broadly where they are for the foreseeable future here (Severn Estuary Shoreline Management Plan – Wentlooge ). However, the shoreline management plan does note that the existing defences will ‘come to the end of their serviceable life in this epoch’ (2025 to 2055)’ and will need replacing, presumably at some significant cost. The Plan suggests creating new intertidal habitats to both improve defences and compensate for habitat loss from coastal squeeze around the estuary. By the end of the century, this coastline could look very different indeed.

What won’t change is the significance of this place. It remains a unique and deeply valued coastal landscape, rich in history and identity, as well as in ecological importance. Any proposals to alter it must face thorough scrutiny. After all, as I’ve found out from researching this article. we’re just one chapter in a much longer story of people living with and, indeed sometimes against, the Severn Estuary. And it’s up to us to make sure the legacy we leave behind is one that future generations can look back on with pride.

Photo: The rich muds at Peterstone Wentlooge

Further information

History of the Levels and its drainage system

Gwent Levels Historic Landscape of Outstanding Historic Interest in Wales – a brief description of the key aspects which contribute to this areas’ historic character.

The Origins of the Gwent Levels drainage system in the medieval period – an online presentation by Professor Stephen Rippon

A history of the drainage of The Gwent Levels

Beyond the seawall – a guide to exploring the intertidal zone along the Gwent Levels

Levels lingo – a guide to the drainage and other local terms used on the Gwent Levels

The Great Flood of 1607

The day the sea came in – 1607 on the Gwent Levels – a children’s story based on Rose’s research

Catastrophic Wave Erosion, Bristol Channel, United Kingdom: Impact of Tsunami?

The Bristol Channel floods of 1607 – reconstruction and analysis

Estuary perspectives

At the ‘heart’ of the estuary – between the bridges aboard PS Waverley (Waverley walk)

Introduction

It’s been a busy month. Between music courses and our annual holiday, unfortunately, I haven’t had the chance to spend much time exploring the estuary’s shores. Instead, I’d like to share some of my favourite moments from walks over the past year, focusing on a few aspects I’ve found especially fascinating. I hope these reflections might inspire you to head out and discover the estuary for yourself.

Tide scapes

I’m continually struck by the way the tides shape and reshape our estuary. One of the year’s highlights was our almost ‘private’ viewing of the Severn Bore at Alney Island in spring – a truly unforgettable sight. I’ve also been captivated by the intricate patterns left behind on the intertidal flats, and the remarkable archaeology preserved in the estuary’s muddy shores.

The bore arriving at Lower Parting, Alney Island (Bore walk)

Mud cracks on the current foreshore (Beachley to Sudbrook walk)

Mythical beasts along the muddy shores (Severn Bridge walk)

Wonderful contrasts on the foreshore near Lavernock Point (Penarth walk)

The silver shore at Goldcliff which holds many historical and archaeological treasures (Newport Wetlands to Goldcliff walk)

Islands

The estuary’s islands have a quiet, enduring allure. They feel almost like old friends, following you around the estuary, sometimes popping up in unexpected places and challenging your sense of geography! Steeped in history, they also provide sanctuary for rare, and at times unique, plants and wildlife. I particularly enjoyed our visit to Flatholm last autumn and discovering some of the challenges of island living and discovering Wales’ most southerly pub, the Gull and Leek!

The rarely seen seaward shores of Steepholm from a recent cruise onboard PS Waverley (Waverley article)

A different geography – a distant view of the Holms from Sand Point (Sand Point to Brean Down walk)

Wild leeks on Flat Holm with distant views across to the Somerset coast (Flat Holm article)

The bridges

And then, of course, there are the bridges. I hope you’ll forgive me for including yet more photos, but given the Severn Estuary Partnership’s logo, to me they are part of what defines this place. I’ve loved exploring both bridges from many different perspectives, though walking across the Severn Bridge last summer on one of the hottest days of the year stands out above all. From that lofty—if deafening—vantage point, I was struck not only by the elegance of its engineering, but also by the sweeping, unforgettable views across the estuary.

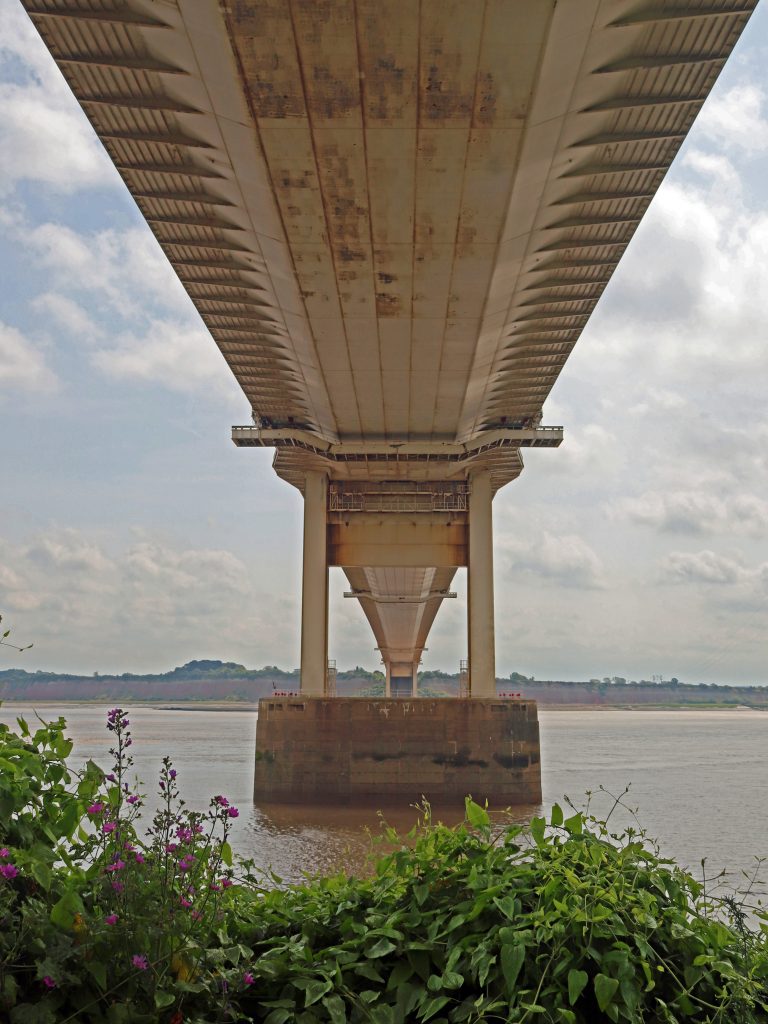

A new perspective of the Prince of Wales Bridge – from below – near Sudbrook (Beachley to Sudbrook walk)

Heading towards the second tower on the Severn Bridge (Severn Bridge walk)

Heading towards the second tower on the Severn Bridge (Severn Bridge walk)

A distant view towards the Prince of Wales Bridge across the mudflats from the Severn Bridge

The last 30 years

As we’ve been celebrating our Partnership’s thirtieth anniversary, I’ve found myself reflecting on the many changes the estuary has seen over this period. Perhaps the most visible transformations have been along its urban shores, where once-decaying docklands have given way to vibrant waterfronts in our port cities and towns. Even more remarkably some of our former industrial shores, such as the Newport wetlands, have been transformed into wildlife havens. Many of the estuary’s resorts, too, have been refreshed, with piers restored and promenades revitalised. Yet these bright new façades sit alongside more sobering shifts. Concerns over water quality and declining fish stocks have curtailed some of the estuary’s traditional activities, making it harder to imagine the close maritime ties of previous generations.

The construction and opening of the Second Severn Crossing—now the Prince of Wales Bridge—in 1996 reshaped the geography of the estuary, strengthening physical connections across its shores. Political changes brought about by devolution have introduced new challenges for its integrated management. Of more concern still is the creeping spread of development at the edges of our settlements alongside the growing threat of climate change. It is little wonder that so much of the estuary’s shoreline now bears the marks of new and strengthened flood defences.

Evening light across the RSPB Newport Wetlands reserve, once a former industrial site (Newport wetlands walk)

Penarth Pier bathed in the evening sunshine (Penarth walk)

The Pierhead Building and the Senedd (the seat of Welsh Parliament, Senedd Cymru) at the heart of Cardiff Bay (Cardiff Bay walk)

Victoria Dock is one of the most imposing dockland restoration schemes around the estuary, particularly as much of the maritime and industrial heritage lies at the heart of the regeneration (Gloucester walk)

The beautifully restored Clevedon Pier from the deck of PS Waverley (Waverley article)

Sea defences at Severn Beach with distant views of Avonmouth (Aust to Severn Beach walk)

Further reflections and conclusions

I hope you’ve enjoyed these reflections on my walks along the estuary so far. Its shores are full of variety, and each walk seems to reveal fresh insights into its history, its communities, and its natural environment. If you have suggestions for stretches I should explore next, or know local people whose perspectives on the estuary would be worth sharing, I’d love to hear from you. Please get in touch via the SEP email: Severn@Cardiff.ac.uk.

The dramatic evening skyline of Cardiff from offshore on the PS Waverley, summer 2025

And the Point is – exploring Sand Point and Brean Down

Rhoda visits two of our longest natural piers extending into the estuary, discovering their past role in strategic defence and their present-day value as open spaces for nature and wellbeing.

Looking towards Weston-Super-Mare with Sand Point in the mid-distance from Brean Down

Introduction

Sand Point and Brean Down – two of my favourite spots on the estuary – and a great chance to visit both alongside our annual forum in Weston-super-Mare! With no students to oversee, no tricky fieldwork to organise, and no grumpy coach drivers to deal with, Geoff and I set out to rediscover the charm of these places in relative peace – and in surprisingly good weather, too. Armed with a wealth of insights from the forum, and thoughtful perspectives from Annemieke Waite, the North Somerset Councillor who’d opened the event, I hope you enjoy reading about our half-day adventures – and maybe feel inspired to explore them for yourself sometime soon.

Weston’s Grand Pier from Brean Down

Excursion one – Sand Point

Driving along Beach Road in Sand Bay, with the sea largely obscured by vegetated dunes and hedgerows, gave little hint of the landscape beyond. But after a short climb through woodland, we emerged onto the broad grassy ridge of Sand Point, and were rewarded with sweeping views across and up the estuary. What a panorama! Clevedon, Newport, Brean Down, the islands (including Denny Island, of course), the bridges and even The Garth —the hill just behind our home in North Cardiff—were all clearly visible. No wonder this spot held such strategic importance for past generations—even, it seems, as far back as the late Neolithic or Bronze Age. As I watched white, fluffy cumulus clouds scuttle across the sky, casting flickering shadows over the reddy-brown, turbid waters of the estuary, I found myself wondering how the scene might have changed over time. While the settlements, industrial sites, and other human landmarks are relatively recent and the extent of the estuary’s waters may have migrated over time, the low-lying, gently sloping dark silhouettes of the hills framing the estuary have stood here for millennia.

As we walked further towards the Point, the views became even more spectacular. On our stroll, knolls of weathered limestone rose sharply above us, their jagged forms resembling the worn teeth of some long-extinct creature emerging from the estuary’s mud. The rising bluster of the wind lent an uncanny sense of movement to the landscape. In reality, these jagged crags of Carboniferous Limestone are the remnants of a shallow tropical sea, formed when this part of the world lay near the equator. Like many sites around the estuary, the limestone here is rich in fossils, containing the remains of corals, crinoids (sea lilies), and other long-extinct marine life. These limestones are also distinctive because they’re more resistant to erosion than many other rocks around the estuary. As a result, they tend to form the tips of most of our headlands and islands —something I always enjoyed pointing out to student groups over the years.

Further along the path towards the Point, increasingly craggy limestone outcrops began to intersect, and eventually merge with, our path. With the wind picking up, walking became increasingly difficult, so, I decided to stay put and take in the panoramas and search for fossils. Whilst the fossil hunt proved fruitless, I did enjoy the sweeping views out to the Holms and the silvery sheen of the calm waters beyond. As the tide receded across Sand Bay, I noticed the deep, meandering channels etched into the mud as they wound their way to the sea—and found myself reflecting on the ever-changing nature of such features. Yes, once a Physical Geographer, always one!

Sand Point Trig. Point overlying a late Neolithic/Bronze age site

View up the estuary from the rocky outcrops on Sand Point

Walkers at Sand Point with distant views of the Holms

Meanders across the extensive mudflats of Sand Bay

The broad pebble beach at Middle Hope – July 2025

A much greener landscape around Middle Hope, Summer 2021

Looking down on the green beach towards Kewstoke with the ‘sand’

With time on our hands— no students to herd or coach to rush back for —we walked over to Middle Hope; an extra bonus. This delightful, unspoilt pebble cove never disappoints. Today, though, the scorched golden grassland on the surrounding cliffs stood in stark contrast to earlier visits, when the cliff tops were covered in lush, velvety green. No carpets of golden buttercups, but a few resilient wildflowers, including bright stands of ragwort, popping out from amongst the dried grasses. Sorry, I’ve no photos of these – they were swaying too wildly in the breeze!

We didn’t explore the beach’s geology on this occasion, but standing on the cliff top I was reminded of the excitement of past student visits, when we’d searched for volcanic rocks here. Yes—volcanic rocks on our estuary! This cove hosts a fascinating range of rocks, including pillow lavas—pillow-shaped rocks formed by submarine volcanic activity, much like the eruptions still occurring off Hawaii today. It’s no surprise this site is protected as a Regionally Important Geological Site (RIGS) for its exceptional geological value.

It’s a particularly special place for Annemieke too, who shared one of her most cherished family memories from a cold blustery day last winter. The day was especially meaningful as her ‘extended family spans all ages and is geographically quite spread out’, so ‘it was wonderful to reconnect with loved ones we don’t often get to see.’ After walking all the way out to the Point, they’d enjoyed ‘thermos flasks of hot chocolate’ as they ‘sat on the rocky beach sipping warm drinks while the children searched for seaweed and collected pebbles.’ Returning to the car park ‘with heavier pockets, they’d got back ‘just in time for hot dogs being cooked up by one of our family members.’ I can almost smell those sizzling sausages!

As we made our way back to Sand Bay, we looked out over the wide expanse of green saltmarsh below and couldn’t help but question the name Sand Point—surely a bit of a misnomer! But as the photo shows (and as I’ve seen on previous visits), there really is sand at the southern end of the bay. This is here partially thanks to a major beach nourishment scheme in 1983–84, following the infamous 1981 storm that caused severe damage along much of the low-lying Somerset coast. This was one of the first large-scale projects of its kind in Britain: over 600,000 tonnes of sand were dredged from the Severn Estuary and pumped onto the beach, raising it by around three metres at the sea wall (Source). There’s also been more recent work at Uphill which Annemieke was keen to point out. Here fencing has been installed in front of the sand dunes to help strengthen and stabilise them. She hopes this will not only improve flood protection but also enhance the biodiversity and ecological quality of this important natural habitat—one that has, sadly, been significantly eroded around the Bristol Channel and Severn Estuary.

Excursion two – Brean Down

After a day of talks and discussion at the Severn Estuary Forum—held, fittingly, on Weston’s Grand Pier, seemingly floating above the tidal muds of Weston Bay—it was a real pleasure to get outside to experience the estuary firsthand again. However, from the outset, it was clear this would have been a very different outing from Sand Point. The sheer number of parked cars and people milling about on the beach set quite a different tone. I’d also forgotten just how large Brean Down is—but was quickly reminded as we began the steep climb up the long flight of over two hundred steps to reach the top of the limestone grassland ridge. I made it to the top, with a few welcome pauses to admire the beautiful wildflower displays edging the path. Thistles, mallows, and scabious swayed gently in the breeze among the brilliant white limestone rocks, their pinks and mauves blending like a natural wildflower garden. Thankfully too, the ever-expanding views over Brean Sands and the sweep of the Bristol Channel provided ample encouragement to keep going.

One of the many colourful floral displays along our route

We crossed to the northern side of the ridge and followed the old military road that leads to Brean Down Fort. As we admired the sweeping views over Weston Bay—its piers stretching out below and Sand Point visible in the distance—a herd of brown and white cattle suddenly emerged out of the bracken. With their large collars, they looked almost alpine—as if fitted with cowbells. But these were, in fact, solar-powered GPS collars, part of an innovative virtual grazing system designed to contain cattle within designated areas and facilitate conservation grazing. As the animals near the boundaries, they hear an audio signal; if they continue, a mild electric pulse gently deters them. This relatively new technology allows the National Trust to manage grazing across the Down more precisely, mimicking the patterns of traditional free-roaming herds. It supports the health of the limestone grassland by promoting biodiversity through targeted grazing. The same ‘NoFence’ system is also in use at nearby Crook Peak, where it’s helped monitor animal welfare too and with GPS ‘heat maps’ here, the Trust has also learnt more about how the cattle behave and move in different weather conditions. Quite remarkable!

An eco-cow grazing on the bracken northern slopes of Brean Down

The strategic significance of Brean Down’s headland was unmistakable as we approached the imposing ruins of Brean Down Fort—still formidable, even in bright sunshine. This was one of a series of Palmerston forts built along the English coast, including five in the Inner Bristol Channel, commissioned by Lord Palmerston (Prime Minister from 1859 to 1865) in response to the perceived threat of a French invasion. In the heat of the midday sun, we were glad to find some shade as we explored the ruins and studied the many informative exhibition boards dotted around the site. These offered a glimpse into the rather bleak living conditions once endured here, as well as its impressive Victorian military technology. In the end, Brean Fort never saw action and was widely regarded as an expensive folly. However, the site was later reused during the Second World War as a coastal artillery battery and a test location for experimental weapons—including, remarkably, trials of a bouncing bomb.

The Palmerston Fort at the tip of Brean Down

One of several formidable gun emplacements within the fort’s remains

The Point at Brean Down – a Second World War launching rail for testing seaborne weapons and a searchlight for looking northwest

Enjoying sea views at Brean Down

Happy memories of a Marine Geography field trip in the summer of 2021 at the end of COVID!

After climbing up onto the Down in the glare of the summer sun, past strangely photogenic WWII lookouts and decaying fortifications, we paused to take in the majesty of the Channel and I reflected on earlier visits with SEP colleagues and student groups. All happy memories, and all, it seems, on similarly sunny summer days. I’m not sure if bigger is better when comparing Brean Down to Sand Point, but on such a clear, fine day, the views from Brean’s summit were undeniably spectacular. We could still make out the Severn bridges far in the distance, but now Steep Holm appeared much closer, framed by the distant South Wales coastline. To the south, the wide arc of Bridgwater Bay unfolded, and the Somerset Levels stretched seemingly forever before us—punctuated only by the ‘islands’ of limestone hills like Brent Knoll, not surprisingly another site of ancient human settlement.

As we made our way back along the hump-backed ridge, scorched grasslands underfoot, it was hard to imagine ancient communities living on this exposed promontory. Even today, wildflowers swayed vigorously in the coastal breeze and gnarled, wind-blown trees—more like ‘bad hairdos’ than natural features—offered a clear reminder that this exposed headland suffers the full force of the prevailing southwesterlies. And yet, just like at Sand Point, a number of finds from Bronze Age and Roman settlements dotted around the headland suggest people have lived here for millennia with. Indeed, we later discovered when looking at the National Trust’s map, we’d walked across an ancient field system and close to a Roman temple!

Umbels wafting in the strong coastal breeze

As we made our way along the ridge, striking limestone crags on the headland’s steeper southern slopes served as a reminder of Brean Down’s shared geological heritage with its northern sister, Sand Point. There was no chance of fossil hunting here, though—not with those sheer drops to Brean Beach! No intricate sand art to admire, as there’d been on previous visits either, but the views were still quite absorbing. From our lofty, almost toy-town vantage point, we could spot sunbathers tucked behind windbreaks, beach games in full swing, and even an ice cream van parked directly on the sand. Just beyond the line of riprap, where once there’d presumably once natural dunes, rows upon rows of static caravans and chalets stretched out, a clear reminder of Brean’s long-standing role as a holiday destination. Indeed, Fred Pontin had clearly seen the site’s potential when he opened his very first Pontinsholiday camp here in 1946, repurposing a former WWII US Army base. Today, even with the temporary EDF take over of the Pontins site as it’s used to house 900 Hinkley Point workers, Brean still ranks as the UK’s second largest camping and caravan resort, a fact that became instantly apparent as we returned to the hustle and bustle of the car park at the bottom of the steps, at the end of our excursion.

Looking along kilometres of Brean beach and the Somerset Levels from the ridge

Brean beach art in progress, Summer 2021

Back at beach level at Brean – quite a contrast to the peace of the Down!

Further reflections and conclusions

It’d been such a pleasure to revisit Sand Point and Brean Down after quite a few years—especially as they’re such familiar landmarks to us, often seen from our regular Welsh vantage points in Penarth and Barry. These striking headlands stretch out like twisted fingers across the muddy bays, rising from the low-lying coastal plains and levels to offer sweeping views of the surrounding landscape, the estuary, and the Channel beyond.

It’s fascinating to reflect on how people have valued and used these places over time. Once home to ancient communities, these headlands were prized for their strategic military importance over thousands of years. In contrast, in our tech-driven and increasingly built-up estuary, it’s their wildness and far-reaching views that we now treasure most. Even on our blustery visits, we’d found a welcome sense of peace and quiet. We owe a great deal to the National Trust, whose decades of conservation work have helped protect these landscapes for everyone to enjoy. The bays between them—often mocked for their shallow seas and mud—have a charm of their own. Indeed, Annemieke values the ‘expansive views across the estuary’ these provide and finds the scenery, which ‘is never quite the same twice’, beautiful ‘especially when the tide is far out and the sand seems to stretch endlessly.’

As she noted in her welcoming speech at the forum, ‘few places in Britain carry such a complex mix of environmental, economic, and social importance within such a short stretch of coast. This gives us a rich canvas — but also a challenging one.’ Balancing priorities is no easy task, especially where communities ‘live with the very real risks of flooding and coastal change, made more urgent by sea level rise and climate change where nearly 40,000 properties are at risk.’ There’s clearly a need ‘for continued investment in tourism and protection of the rich Victorian and maritime cultural heritage’ of the area. But then there’s the ever-present question of tidal energy generation—an issue never far from discussions along this stretch of coast.

Personally, I’m rather relieved that the long-debated Cardiff – Weston Barrage proposal has been shelved. The 16 km structure, planned to stretch from Lavernock Point near Penarth to Brean Down, would have dramatically altered this part of the estuary. That said, interest in harnessing the tidal energy of the Bristol Channel hasn’t disappeared. In fact, following recent recommendations from the Severn Estuary Commission, attention is shifting further west—towards areas like West Somerset, where the tidal range remains significant but the potential environmental impact should be lower. Whether such sites fall within the estuary proper is up for debate. While Sand Point and Brean Down are often seen as marking the seaward boundary on the English side, our very own Severn Estuary Partnership has traditionally used a more flexible definition of the Severn Estuary, extending the boundary along the Somerset coast.

Sounds like the perfect excuse for more exploring—and I’ll be sure to report back!

One of the many wind-blown trees on Brean Down, which Geoff described as ‘the Marge Simpson look’

Further information

Do you have a passion for environmental communication and a talent for engaging diverse stakeholders? The Severn Estuary Partnership (SEP) is looking for a dedicated and dynamic Communications Officer to enhance the visibility and impact of the partnership’s work in promoting the sustainable management of the Severn Estuary.

The Severn Estuary Partnership is a collaborative initiative based in Cardiff and hosted by the School of Earth and Environmental Sciences at Cardiff University. Our mission is to foster cooperation across a broad range of stakeholders, including government bodies, local communities, environmental organisations, and industry representatives, to support the health and sustainability of the Severn Estuary.

As the Communications Officer, you will lead SEP’s strategic communications efforts, managing channels, creating compelling content, and coordinating campaigns to reach diverse audiences. You will collaborate closely with partners to enhance awareness and engagement with SEP’s initiatives, working on projects that highlight the importance of the estuary’s environmental and community value.

The successful candidate will be an experienced communications professional, ideally with a background in science or environmental outreach. They will possess strong interpersonal and strategic communication skills, with the ability to convey complex information to diverse audiences including policymakers, community groups, and academic stakeholders. Competency in digital content creation, media engagement, and stakeholder coordination is essential. The candidate will be adept at managing multiple projects independently, using creativity and initiative to enhance the visibility and impact of the Severn Estuary Partnership. A proactive, collaborative mindset and a commitment to continuous learning and professional development will be key.

This post is funded though The Nature Networks Fund, delivered by The National Lottery Heritage Fund in partnership with the Welsh Government and Natural Resources Wales. It aims to support nature recovery and improve the condition and connectivity of protected sites across Wales.

This position is part time (28 hours per week), available immediately and is fixed term until 31st March 2028.

Salary: £33,482 – £36.130 per annum, pro rata (Grade 5)

Informal enquiries may be made to Alys Morris, email: MorrisA18@cardiff.ac.uk

For further details about working in Cardiff University please contact John Evans, email: EvansJ13@cardiff.ac.uk

Date advert posted: Wednesday, 9 July 2025

Closing date: Wednesday, 30 July 2025

To apply, click here.

Between the bridges – Beachley to Sudbrook and beyond

Rhoda returns to the Severn Estuary, this time exploring the shore between the Severn Bridge and the Prince of Wales Bridge, to uncover more tales of river crossings and their lasting impact on the fortunes of local communities. From heritage fisheries and whale bones to gushing springs and the UK’s longest overhead power line span, this stretch of coastline is full of surprising stories waiting to be discovered.

Across the marshes looking towards the Prince of Wales Bridge

Introduction

Another sweltering day was on the cards for my monthly estuary walk. Still, I figured that by doing the ‘mirror image’ of my last route — from Aust to Severn Beach — but this time on the other side of the Severn, between the two bridges, we might at least find a bit of shade beneath the structures themselves.

Keen to build on the stories we’d uncovered during that previous walk, I set out with Geoff, my trusted companion and husband, to explore the Severn shoreline between Beachley and Sudbrook. Much of our route followed the Wales Coast Path, winding through landscapes so well documented by the Living Levels project.

I hope you enjoy reading about our day out as much as I enjoyed walking and researching it — preferably with a cool glass of something refreshing in hand. (There may even be a few ideas for that later…)

The Severn Bridge from near Beachley Point

Underneath the arches: the Severn Bridge undercarriage

The river crossings – the Beachley Slipway and the Severn Bridge

My attempt at a ‘commercial’ photo shoot!

Beachley – the old and the new crossings

Parking in the shadow of the Severn Bridge alongside a tangle of undergrowth, a ‘Danger: sea wall unsafe – keep away’ wasn’t quite the welcome I’d expected. The Old Ferry Inn which I remember seeing during a photo shoot twenty plus years ago seemed also to have lost its charm despite efforts to renovate part of the building as a conference centre. The Severn Area Rescue Association (SARA) station next door was eerily quiet too, despite various noticeboards highlighting the incredible work that operates out of this otherwise unremarkable building.

Then, we turned to look at what we had come to see — the Beachley to Aust crossing, the other end of the Old Passage that we’d encountered on our last walk. The wide stone ramp of the old slipway sloped gently downward, as if inviting us to step into the chocolate-brown waters of the Severn. No ferry today, though – the last car ferry crossed the estuary here nearly sixty years ago, on the day before the Severn Bridge opened. However, many older people still have happy memories of travelling on this ferry. Kay Powell, a former SEP Chair, excitedly recalled her childhood experiences. In our recent get-together she recounted her summer outing from Cardiff to visit her great aunt in Portishead. ‘The most exciting thing was when my dad got a car, and we’d go via the Aust Ferry. There we could see the sea gently receding. And there we were, counting the numbers of cars back, seeing if we’d get on the next ferry. And actually getting onto that with the turntable and going across to Aust…an amazing experience!’ Kay is one of many generations to have used this historic crossing — a route once travelled by Roman legions and 12th-century monks. As we watched the swirling muddy waters recede at the bottom of the slipway, it was easy to understand though why several fatal crossings had occurred here in the mid-nineteenth century — and why Daniel Defoe reportedly chose to avoid this crossing, opting to travel through Gloucester instead.

This crossing, however, is no backwater. It still serves as the slipway for SARA and other watercraft. During our visit, the slipway also served as a spot for a local angler to fish and a mooring for the fishing boat Helen Louise. Its owner eagerly shared stories of fishing for cod, conger eel and other fish in the Severn and fondly recounted crossing the old ferry as a boy, when he and other kids would hop on and off to catch a ride to the other side. “It hadn’t been the same once the bridge was built, but at least the pilots [many of whom were called Jack] were able to find work operating the toll booths,” he reflected. Later, as I focused on capturing better angles and shadows for my photos, I was distracted by the buzzing of a small drone overhead. Then, to my surprise, a sleek Bentley sports car smoothly glided onto the slipway. The slipway had become the unexpected backdrop for a commercial photo shoot! As you can see, I had a go at some glitzy photos, with moderate success.

Beachley Point – connections

After a short stroll along a leafy track, with occasional glimpses back toward the Severn Bridge, we arrived at a rather scruffy spot near the National Grid’s Beachley Compound, overshadowed by the striking anchor pylon soaring an impressive 148 metres above. At just 10 metres shorter than Blackpool Tower and significantly taller than any of the ‘skyscrapers’ in the cities surrounding the estuary, this pylon — along with its twin at Aust —supports the longest overhead power line span in the UK, stretching an impressive 1,618 metres. We craned our necks to take in the sheer scale of this giant electrical bridge stretching across the Severn!

We hadn’t come to admire the pylon, however — spectacular as it was, but rather to take in the views of the estuary and catch a glimpse of ‘Tracey Island,’ which I first spotted during my sail on the Waverley last summer. After some careful negotiation, avoiding stinging nettles and brambles, we eventually made it to the viewpoint at Beachley Point. Beyond a carpet of brown seaweed and glistening, slippery mud, the faint silhouette of a ruin perched on a rocky hummock came into view—the island known by so many names – Chapel Rock, St Twrog’s Island, St Tecla’s Island…and now Tracey Island, of course! Despite the falling tide, there was no chance we’d attempt to reach the ancient ruins of this medieval holy site today, just as generations of pilgrims are said to have done in the fourteenth century. I could certainly understand why this site once served as a refuge for hermits. However, with so many modern intrusions visible across the mudflats — pylons, warehouses, and other stark reminders of the 21st century, it was difficult to imagine the solitude that once defined this place.

The impressive anchor pylon near Beachley Point

Across the seaweed towards the island of many names

View across the mudflats towards the Wye Estuary

Black Rock – tidal landscapes, lave fishing and estuary connections

After retracing our steps, we drove to Black Rock, where we enjoyed our picnic lunch accompanied by spectacular views of both bridges stretching across the estuary. The scene was made even more striking by the vast intertidal zones laid bare by the low tide. With the mudflats and seaweed-draped rocky reefs exposed, the foreshore revealed a captivating and ever-changing landscape, though a treacherous one, as signalled by the white lighthouse that stands guard over the offshore reef (Charston Rock) hidden beneath the water at high tide. Later, treading carefully, I explored the edge of the marsh and was fascinated by its intricate microtopography. Dense tufts of saltmarsh grass rose on small hummocks, criss-crossed by a network of hidden and shallow hollows, some still holding water. It was a remarkably complex and diverse ecological system — shaped by a long and layered history of both erosion and deposition. Even just inland from the true marsh edge, isolated stems and clumps of cord grass were beginning to take hold, pushing up through the drying cracks in the mud.

View upstream to the Severn Bridge from Black Rock

View downstream to the Prince of Wales Bridge

Cordgrass attempting to colonise the mudflats

Suddenly, we spotted one of the famous lave net fishermen striding across the mud, likely returning from the channel after a session of fishing. He carried his distinctive willow-framed net, just visible in the photo below. Although now a catch-and-release heritage fishery for salmon — somewhat contentiously — this centuries-old tradition is still upheld by a few dedicated local fishermen at this heritage site. According to their Facebook page, the group has built quite a following, and their videos are well worth exploring. You’ll find everything from explanations of how the nets work to footage of their fishing finds, including ancient fish traps, curious debris, most unwanted items, and more. If you’re interested in learning more, they’re hosting a special open day on 25 August. To celebrate this enduring tradition, there’s even a striking, larger-than-life oak sculpture of a fisherman and salmon, carved by local chainsaw artist Chris Wood, proudly displayed near the picnic site overlooking the estuary — a piece we stopped to admire.

A lave net fisherman returning to shore with the Black Rock lighthouse in the background

The Fisherman sculpture at Black Rock picnic site

Nearby, facing out to sea, another sculpture from the People and the Landscape series caught our eye — standing proudly atop the remaining stump where the rail-steam ferry once crossed to New Passage, which we’d visited just a month earlier. The Engineer — a distinguished figure in a smart coat, hat, and walking stick, holding a model of a factory in his left hand. This sculpture pays tribute to all those who worked on the Severn Tunnel, the two bridges, and the seawall that protects the Gwent Levels. It’s inspired by the intrepid and resilient 19th-century engineer Thomas A. Walker, who completed the Severn Tunnel and oversaw the development of the neighbouring village of Sudbrook — where we were to head off to next.

The Engineer sculpture standing proud above the old Black Rock slipway

The imposing Victorian Sudbrook Pumping Station

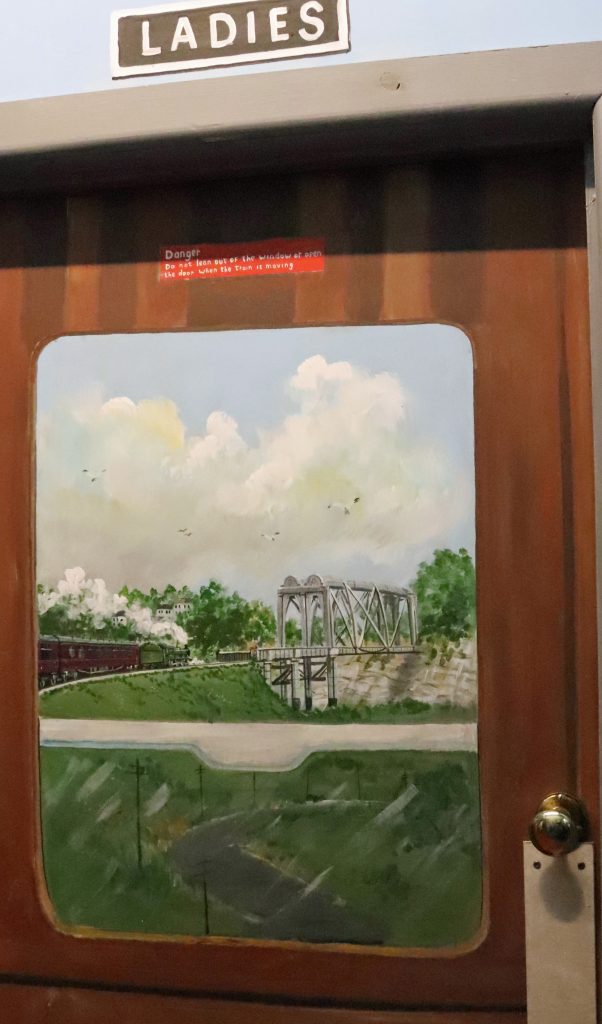

The view on the door of the Ladies toilets

Sudbrook – discovering more Severn heritage

The shade along the leafy path gave us some much-needed relief as the temperature climbed, and it was with a certain relief that we reached the edge of Sudbrook. After passing some nondescript modern developments, we found ourselves on a long street lined with cottages — part of Walker’s workers’ village from the nineteenth century, built during the construction of the Severn Tunnel. With their colourful façades and flower-filled gardens, it was striking to think these homes had once been humble dwellings for the labourers working on this ambitious project – one we still rely on today, as trains whisk us through the Severn Tunnel in under four minutes on our journey to and from South Wales. As we approached the imposing red-brick Sudbrook Pumping Station rising high above the cottages at the heart of the village, we could hear the steady whirring of machinery. No fewer than fourteen pumps are required to keep 50 million litres of water out of the tunnel every day, and, as Network Rail informs us, these must be replaced every three decades. As we learnt later from our visit to the local museum, confronting and containing the ‘Great Spring’ was one of the great engineering feats of the late nineteenth century.

The Sudbrook Interpretation Centre is quite a gem and is worth a visit, although tucked away in the corner of the Sudbrook Non-Political Club, it wasn’t that easy to find. Though we seemed to enter through a back door, we were immediately transported into another world — greeted by colourful murals in the entrance hall celebrating railway triumphs and journeys. Even the toilet door was painted, as you can see below.

The exhibition room, though modest in size, held a fascinating and eclectic mix of local stories and memorabilia that we eagerly explored. Alongside informative display boards lining the walls were towering stacks of scrapbooks, school projects, and old photo albums. Glass cabinets showcased an array of finds from the mud of the River Severn—many with real historical significance. There was even the horn of a medieval cow and a whale bone from a whale that washed up at Sudbrook a century ago, in 1925!

We took our time delving into the material — not only was it genuinely fascinating, but it also offered a welcome cooling refuge from the sweltering heat. I have to personally thank the Caldicot and District Historical Society, not just for curating such an engaging collection, but also for the thoughtful touches like the tea and coffee-making facilities. If only every community around the Severn Estuary had such a valuable and lovingly maintained resource.

The Prince of Wales Bridge – yet another perspective!

After enjoying the cool respite of the museum, we stepped back into the searing afternoon heat to complete our bridge-to-bridge journey — determined to reach the Prince of Wales Bridge on the Welsh side of the estuary by foot. Skirting behind more of the original workers’ cottages, we eventually found ourselves crossing a football pitch by the water’s edge. But this was no ordinary pitch — it stands within Sudbrook Camp, an ancient hill fort likely dating back to the Iron Age. Over the past two thousand years or so, significant coastal erosion has claimed much of the southern ramparts, now lost to the sea. Perhaps something the residents of the extensive new housing estate to the west of the village — partly nestled within the remaining ramparts — should be mindful of, especially given the size of some of the debris scattered along the strand line on the marshes.

With the sun beating down, I must admit I struggled to walk the rest of the path, which, being wide open to the coastal marsh, offered no shade. The ever-changing marshes and sweeping coastal views kept me going, though I found myself increasingly distracted by the roar of traffic growing louder and more thunderous as we neared the bridge. After nearly emptying our water bottles, we finally reached our destination — and the cool shade beneath the bridge’s undercarriage was a truly welcome relief.

Amid the relentless noise of traffic, focusing on taking meaningful photos was a challenge, but I hope the ones that follow convey the sheer scale of this mighty structure from our vantage point — a strikingly different perspective from what we’d seen on the other side of the estuary only a month ago. Here at Caldicot, the bridge twists sinuously across the marshes, stretching into the distance like a giant centipede resting on towering pillars. We savoured our final glimpses through the arches, offering an intriguing view of this impressive feat of engineering, before making our way back to Black Rock — via the wonderful refuge of the Sudbrook Interpretation Centre, of course.

Housing nestling behind Sudbury Camp – note the storm debris on the marsh

The Prince of Wales bridge meandering above the marshes at Sudbrook

Further reflections and conclusions

Whether it’s an unexpected perspective on a familiar place or a fresh angle on a well-known structure, there’s always an element of surprise that keeps us engaged as we explore each stretch of this remarkable estuary — and this walk was no exception. It was far from a mirror image of my previous walk, though there were many similarities and parallels — not least the sweltering heat on both occasions. But new stories had emerged on this side: tales of the traditional lave net fishery, for instance, and the unexpected popularity of the old Beachley slipway as a photo shoot location.

The strategic importance of river crossings — and their influence on the ups and downs of coastal communities — is something both stretches of the estuary share. Sudbrook, for one, quite literally owes its existence to the construction of the Severn Tunnel. Today, it’s a far cry from Walker’s original ‘new town’ plans, but one thing hasn’t changed: the Great Spring still needs taming. Indeed, next time you crack open a Budweiser, Stella, or a pint of Welsh bitter, there’s a chance you’re actually drinking water from that very spring — it now supplies the local brewery at Magor! As for me, after a scorching day out, I gave the beer a miss and opted for a tall glass of my trusty Severn Beach/Pilning cordial, the perfect way to reflect on yet another memorable day by the estuary.

An intriguing perspective through the arches of the Prince of Wales Bridge

Further information

Check out this link for a stunning photo of a bridge section being installed over the ferry slipway at Beachley

Living Levels Loop and Links Walk 5 – Caldicot to Black Rock loop

Sudbrook and Portskewett trails through the ages

The Severn Estuary Forum Programme is out now!

We are delighted to announce the release of the full programme for the Severn Estuary Forum 2025, taking place on 3rd July in Weston-super-Mare. This year, the forum brings together a rich mix of expert talks, panel discussions, and community stories.

Register for the forum and explore the programme here:

Exciting Student Placement Opportunity – Join us in ‘Future-proofing’ the Severn Estuary

We’re pleased to offer an exciting student placement as part of our “Future Proofing the Severn Estuary” project. Hosted within Cardiff University’s School of Earth and Environmental Sciences and funded by the Nature Networks Programme through the National Heritage Lottery Fund, this project focuses on enhancing the protection and resilience of the Severn Estuary Marine Protected Area (MPA).

As a placement student, you’ll play a key role in updating our State of the Severn Estuary Report—a crucial resource for environmental monitoring and decision-making. You’ll help develop an evidence and data collection plan and work directly with stakeholders to identify data needs, gaps and resolution requirements for decision-makers.

You’ll be part of a dedicated and supportive team, gaining valuable experience in data gathering, stakeholder engagement, and environmental reporting. The role offers flexible, blended working and will involve travel across the Severn Estuary area.

This is a fantastic opportunity for a student passionate about marine conservation, sustainability, and environmental data. Applications are open until 20th June. For more information about the role and how to apply, click the button below.

Join us and help shape a sustainable future for one of the UK’s most iconic coastal environments.

Aust Cliffs to Severn Beach: reflecting on the passage of time

Written by Dr Rhoda Ballinger, SEP Chair

Rhoda delves into deep time at Aust Cliffs, visits four estuary crossings from different periods and reflects on coastal change and flood risk around Severn Beach.

Photo: The Prince of Wales Bridge crossing over some of our estuary’s most treacherous waters

Introduction

Since becoming SEP Chair in April 2024, I realised I’d completed a dozen walks, but hadn’t yet explored the shores of several local authorities around the Estuary. With this in mind, I decided to focus my next few walks on filling those gaps. So, this month, having heard about various management projects along the South Gloucestershire coast in recent SEP meetings, I decided to explore the shore between Aust and Severn Beach.

On one of those fine sunny days in early May, I ventured out with Geoff, my husband, to explore the shore between the bridges on the English side of the estuary. Once again to inform my article, I’m grateful to the members of the community for sharing their rich local knowledge and history. Val George has been involved with the Pilning & Severn Beach History Group since its inception in 1999 and Alderman Peter Tyzack, vice-chair of Pilning and Severn Beach Parish Council, is no stranger to SEP, having been Chair of our Steering Group.

Photo: Cattle grazing on the marshes in front of the iconic Aust Cliffs

Photo: The impressive Aust cliffs showing evidence of active erosion

Photo: Mud cracks on the current foreshore

Aust cliffs – a glimpse into deep time

We started at Aust Cliffs, the sister site to the Penarth-Lavernock shoreline which I’d visited on my first e-news walk. I was especially excited to visit these cliffs, renowned for their geological significance. Designated as a Site of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI), they offer one of the most remarkable records of environmental change from around 210 million years ago, when rising seas flooded a once-arid desert landscape. These days they’re a mecca for fossil hunters, containing the famous ‘Rhaetic Bone Bed’ with its incredible wealth of remains of fish and marine reptiles/ dinosaurs. What might we find?

As we neared the shore, the towering cliffs rose above us, showcasing a striking sequence of coloured strata—from red and green marls to cream and white limestones—that was truly impressive. From a distance, it might have looked like a giant slice of sponge cake, but up close, there was fascinating geological detail. White veins jutted out from the ancient red desert rocks, resembling the worn, jagged teeth of some long-lost giant beast. These were made of gypsum, formed when highly salty water evaporated in shallow, temporary lakes (playas), similar to what occurs in the Dead Sea today. Glittering chunks of gypsum lay scattered across the shore like discarded chess pieces, having tumbled from the cliff face above. As we continued along the beach, carefully skirting recently fallen trees, I questioned the official claims of ‘slow’ erosion—prompting me to take a cautious step back. Later, I also wasn’t surprised to learn that for reasons of safety the first classic sketch of this cliff in the 1820s, had been made from a rowing boat offshore!

The beach here quickly morphs into soft mud – and, determined not to have another Severn Estuary mud immersion experience after my Severn Bore visit, I focused on studying treasures within the mid-shore. To my surprise, the muds were a spectacle in themselves. Mud cracks, formed from the drying out of mud as the tide had waned, had created a fascinating display of intricate and complex polygonal patterns. From every angle there was a cubist masterpiece – a shame our visual artist friend, Heather Green, who studies and draws inspiration from our intertidal areas, wasn’t with us.

Having exchanged a few words with a couple of fossil hunters, who were leaving with a plastic bag of goodies, we scoured the beach. No sharks’ teeth or bones from dolphin-like ichthyosaurs and long-necked plesiosaurs today. We had to make do with observing a motley collection of marine shells—mostly fragments of oysters and scallops—from boulders that had fallen from the cliff. With little time or expertise, we couldn’t examine the site’s renowned fossil insect deposits—the richest Triassic insect locality in Britain. As a small consolation, though, a pair of peacock butterflies performed a brief pas de deux as we left.

Old estuary connections: The Severn Bridge and the Old Passage

We carefully negotiated our way over a sea of boulders to get a rare view of the undercarriage of the bridge, now definitely a senior, at sixty years old. Here, it was at its most impressive, rising elegantly above the still, brown waters of the Severn. However, whilst the photo might suggest a peaceful, tranquil view, we struggled to appreciate the scene against the constant roar of traffic. More disturbing, however, is the news today, that new weight restrictions have come into force on the bridge. Hopefully, a technical solution will be developed soon to keep this vital bridge safe and functioning.

Moving along the shore toward Old Passage, there were more mud cracks, mysterious wooden structures jutting out into the water, and countless views of the bridge—keeping my camera busy the entire time! Before too long, the boom of motorway traffic gave way to the enchanting calls of reedbed birds and the graceful reeds, wafting gently in the light breeze, provided ever more photo opportunities.

We emerged out of the reed beds to spot the decaying wooden skeleton of the old slipway, which stretched across the marshes and mudflats before disappearing into the calm, brown waters of the Severn. This was the site of an ancient estuary crossing, dating back at least to Roman times—or possibly earlier—serving as a vital, though sometimes treacherous, link between Aust and the Beachley Peninsula. Given the calm still waters on our visit, it was difficult to imagine how perilous this crossing had been. Despite fatal accidents, a small car ferry had operated here until the Severn Bridge opened in the 1960s.

Memories of the ferry terminal live on, immortalised by Bob Dylan’s visit and featured on one of his album covers, as well as in the 2005 documentary No Direction Home. In my husband’s family album, there’s also a photo of the MV Severn Queen—one of the last ferries to serve here along with her sister ship, the MV Severn Princess, which carried Dylan across the estuary. No longer here, but now lying at rest on the other side of the estuary at Chepstow, we had to make do with exploring what remains of the slipway structure and its rusting artefacts.

Photo: A rare view of the undercarriage of the Severn Bridge at near low tide

Photo: Looking through the reed beds back at the Severn Bridge

Photo: The wooden remains of Old Passage, marking the former ferry route across the Severn

Photo: MV Severn Queen, one of the three last ferries to use Old Passage (A.L. Ballinger)

Between the bridges – agriculture and ecology dominate

Along Passage Road and further on along the Severn Way atop the flood embankment, we enjoyed some ‘typical’ estuary landscapes – great wide-open vistas across broad, low-lying verdant marshes with distant views of the bridges. There were also wonderful hedgerows, adorned with frothy white cow parsley and extensive patches of white scurvy grass brightening up the marsh edges. Agricultural pastureland gave way to conservation areas, including the Pilning Wetlands, created and relandscaped from sections of the old military firing range and sheep grazing fields at Northwick Warth. Here, as the website suggests, a telescope would have been useful. I just made out a flock of Canada Geese, but frustratingly, the distant waders and dabbling ducks eluded me. In season and with proper equipment, I’m told you can spot a wide variety of birds here, including curlews, dunlin, and snipe. Indeed, over two hundred different species have been recorded including rare Glossy Ibis and Red Necked Phalarope. No wonder so many birders were out and about!

As we approached New Passage, I was delighted to be able to recognise a couple of shelduck resting on the muddy banks of Chestle Pill, a deep tidal creek which meanders across the marsh. The scale of the extensive engineering around the creek pointed to serious flood risk concerns though. As I later discovered the recent multi-million-pound Avonmouth and Severnside Enterprise Area (ASEA) Ecology Mitigation and Flood Defence Project has provided for lots of new defences including innovative design features such as the see-through glass barriers you can see along this stretch.

Photo: Floral interest along the way – wonderful hedgerows of wild cow parsley

Photo: Chestle Pill at the southern edge of Northwick Warth

Photo: See-through coastal defences along Aust Wharf Road

Photo: The remaining stump of New Passage with the Prince of Wales Bridge in the distance

Photo: Severn Lodge Farm, one of the remaining old buildings at New Passage

More recent estuary connections: New Passage & the Prince of Wales Bridge

We continued along the path that runs atop a stark stone-and-concrete sea wall, tracing the line of the old Binn Wall—built in 1815 to replace earlier 17th-century defences. Although its appearance on 19th-century maps might suggest it was indestructible, the Binn Wall has been upgraded and raised several times in response to flooding. Today, the newly improved wall serves as a promenade, offering locals and visitors sweeping views of the Prince of Wales Bridge. As we ambled along, we noticed a small kink in the seawall. Goodness – was this New Passage? It’s certainly nowhere near as eye-catching as the relic structures at Old Passage. However, as we were to learn from the informative plaques and the New Passage Heritage Trail, its history is every bit as fascinating.

New Passage offered a more direct crossing and, although there’d been on-and-off operations here since the early 17th century, it was the arrival of the Bristol and South Wales Union Railway in 1863 that truly transformed its fortunes. Locomotives pulled carriages onto a wooden jetty stretching well out into the estuary, allowing rail passengers to easily board the ferries to Portskewett. Despite this, the crossing was notorious for its harsh conditions. Indeed, Thomas Telford famously described it as “one of the most forbidding places at which an important ferry was ever established.” Delays were frequent – so much so that a large hotel was built for waiting passengers. However, it was the opening of the Severn Tunnel in 1886 which brought ferry services here to an end. The pier was dismantled shortly afterwards. Today few original buildings from New Passage’s heyday remain although, Severn Lodge Farm—once a lodging place for visitors and notable for its impressive twenty-four chimneys— is still a local landmark.

Beyond New Passage, we eventually reached the Prince of Wales Bridge, which was even more imposing at close quarters than at a distance. Amid the roar of traffic overhead, we followed the track beneath the bridge, taking in its immense scale from this dramatic new perspective. Wow! The supporting pillars are indeed huge and the whole structure is so much sturdier than its younger upstream cousin. It’s almost as if the Severn Bridge is the graceful ballerina, and this, the tough, almost invincible rugby player. There were plenty of photo opportunities too as we tried to capture the bridge’s graceful, almost serpentine curves and its striking presence. Then, just beyond the bridge, we spotted the famous iron pipe, which, as Peter Tyzack later explained, is the outfall for fresh water pumped from the Severn Tunnel.

Photo: A new perspective of the Prince of Wales Bridge – from below!

Photo: The outfall pipe from the Severn Tunnel with the PoW Bridge behind

Photo: The green shore fronting the sea wall at Severn Beach

Photo: Shirley’s café – almost the sole reminder of Severn Beach’s heyday as a seaside resort

Severn Beach – Seaside tourism, suburbia and industrial change

Following the promenade, we were joined by a growing number of fellow walkers as we approached Severn Beach. I was slightly disappointed, though not at all surprised, to find it wasn’t a traditional, touristy beach. After all, this is the Severn Estuary! Instead, mud, shingle, saltmarsh and even more mud. A great haven for wildlife and birdlife though, not that we had time to study these now, having spent more than a few minutes en route gathering elderflowers to make my annual cordial. We couldn’t miss the hulks of driftwood—entire tree trunks—strewn along the shore, stark reminders of why such substantial sea defences are needed here. Nestled, perhaps even cowering, beneath the towering defences, rows of neatly laid-out modern housing estates stretched as far as the eye could see.

Severn Beach once truly lived up to its name, drawing thousands of visitors each summer—as we learned from the display inside Shirley’s Café, one of the few remaining buildings from the village’s heyday as a seaside resort. It even aspired to be the Blackpool of the Southwest! Thanks to the vision of local entrepreneurs and the opening of the station in May 1922, Severn Beach became the go-to place for day trips for people from Bristol and beyond. Development opportunities, akin to those along the Costa Blanca in the 60s, were suddenly unleashed. A grand hotel, cafés, pubs, shops and wooden bungalows sprung up. Attractions, including a fun fair, boating lake and the much-loved Blue Lagoon swimming pool, alongside donkey rides, beauty contests and dance competitions drew in the masses. There were a few issues, however—local hearsay claims that the sand brought in to improve the shingle beach was washed away by the first high tide. Then, after a highly successful second season in 194, the highest tide in over a decade caused widespread damage, turning wooden bungalows into floating houseboats. It was, however, the development of the motor car and the rise of foreign holidays in the 1960s which caused the resort’s final demise. The boating lake and Blue Lagoon were demolished in the 1970s, ironically making way for improved sea defences to protect the growing number of houses in the area.

Val and Peter, like much of the local community are certainly proud of the area’s history. We followed Val’s local history group’s heritage trail, discovering a series of informative plaques and locating key sites from the resort’s past, including the boating lake and Blue Lagoon—now peaceful, grassy seafront areas. With the current popularity of open-air swimming, some residents might hope to see the lido restored. For now, the resort’s revival includes the recently refurbished (2018) Tea Cottage and the anticipated opening of the Severn Beach Miniature Railway, later this year.

Standing at the end of the promenade, looking toward Avonmouth as our walk concluded, we took in a starkly different, more industrial landscape—where wind turbines, chimney stacks, and large factories dominate the skyline. Peter notes this area has changed quite considerably over the last few decades. Thanks to major investment in improved transport infrastructure, this area has been transformed into a key energy hub. It now hosts the 1,140 MW Seabank gas-fired power station and the Severnside Energy Recovery Centre, which converts waste into electricity enough to power roughly half the homes in South Gloucestershire. According to Peter, there’s an old outfall pipe from the 1960s Imperial Chemical Industries (ICI) Severnside Chemical Plant and fertilizer factory, which operated until the early 1990s. Apparently some of the foreground isn’t natural: Peter explains that much of it is made up of demolition waste, likely dumped there cheaply and conveniently to serve as a basic sea defence. He also notes significant accretion along the coast here, especially since the construction of the Prince of Wales Bridge. I wonder: was this an intended effect, or a lesson we should consider for future large infrastructure projects in the estuary?

Photo: looking across the foreshore at Severn Beach towards Avonmouth